The Revolt produced the earliest known articulation of a modern sovereign Indian political identity, in the form of Azimullah Khan’s iconic composition: Hum Hai Iske Malik, Hindustan Humara. Composed by a Muslim leader, it spoke about an Indian identity based on unity of all religions and communities, especially between Hindus and Muslims. The song was infused with the spirit of unity that guided the Revolt: Hindus and Muslims chose each other as leaders, and fought shoulder to shoulder against a colonizing force.

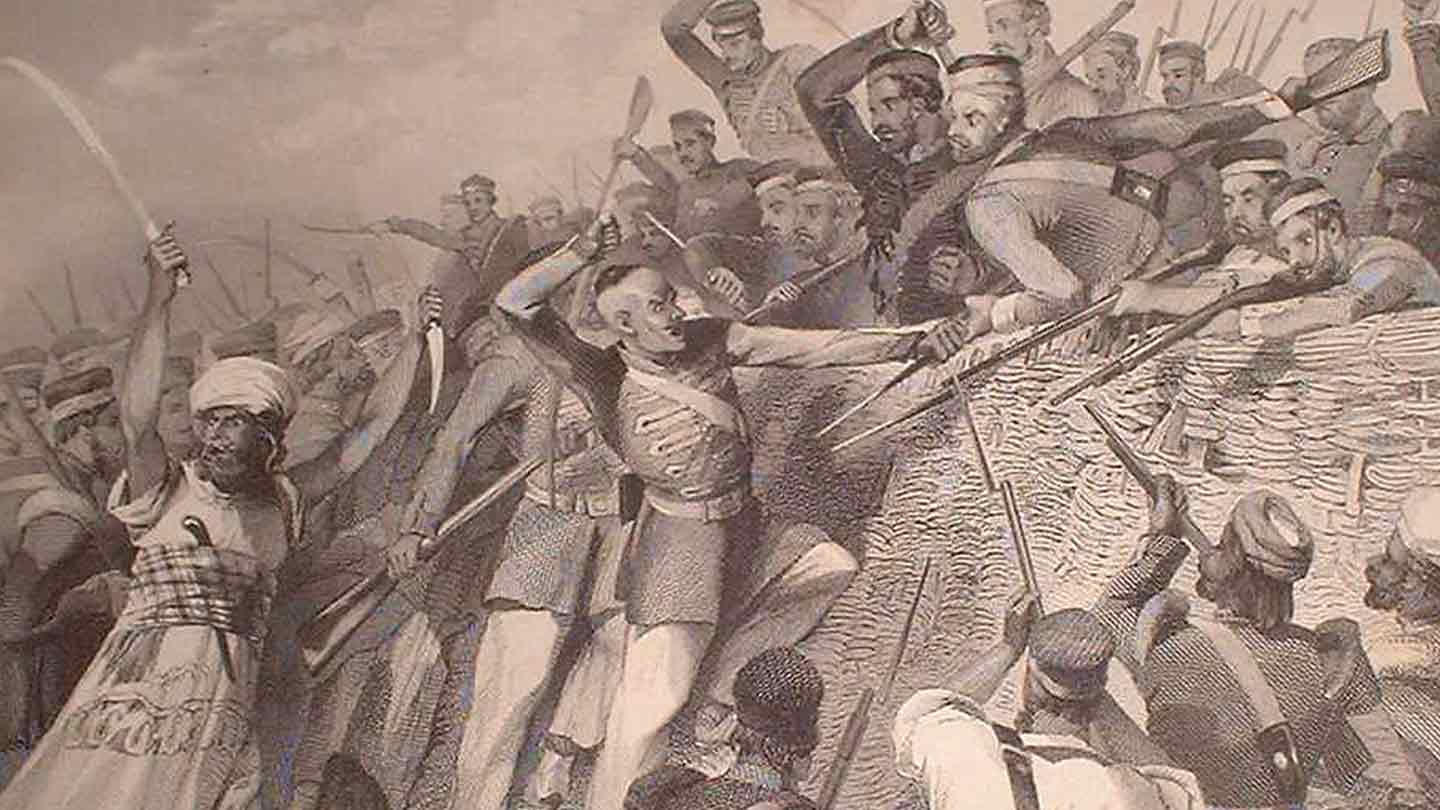

Other than the Hindu-Muslim unity, the Revolt also stood out for its mass character, social diversity and unprecedented scale. All these together shocked the Britishers. The British Crown ended Company rule and started governing India directly after suppressing the Revolt.

From here onwards, they deliberately introduced ideas of racial superiority and racial segregation as dominant ideologies of the empire. The Indians now came to be projected as barbaric, as people who must be controlled. This was a way of suppressing India’s political agency whose powerful display almost cost the British the empire in 1857.

1857 onwards, we find a conscious effort by the British government to divide Indians on religious lines as a matter of policy. Religious fault-lines were deliberately played up in the post-1857 colonial discourse, and religious conflict came to be projected as a key element of Indian “barbarism”.

Despite the Revolt’s composite character, or rather because of it, the Britishers blamed the Muslim community for conspiring to destabilize their rule, and began to exclude them from the freshly constituted structures of governance. At the same time, they pretended to be benevolent to Hindus, and attempted to “befriend” Hindus as a community. This created a political and economic chasm between the two communities, and eventually tore the country apart.

Far from being a revolt of a few disgruntled kings, queens and feudal lords, 1857 was a national uprising of peasants whether in soldiers’ uniforms or without, artisans and small traders, and other sections of the Indian people cutting across caste and creed. The appointment of the titular Mughal ruler as the leader was nothing more than a tactical move.

While several Indian princes played a major role in eventually betraying the rebels, the princes who emerged as rebel leaders invariably connected with the masses. Kunwar Singh from Bihar is a good example. He led a mass rebellion in Shahabad, which was remarkable for the armed guerrilla warfare of peasantry against imperialism, its Hindu-Muslim unity, and its spirit of democratic equality towards the peasant masses and oppressed castes.

The mass character of the Revolt arose from the events which preceded it. For almost two decades preceding the Revolt, its epicentres had witnessed militant movements of Adivasi peasants against the colonial-feudal nexus of exploitation and oppression.

The Revolt of 1857 was followed by several such movements such as the Santhal rebellions which presaged the worker-peasant-Adivasi agitations of the 1920s and 1930s. The Revolt was thus a precursor to the 20th century freedom struggle in which revolts against societal exploitation combined with revolts against colonial rule and tireless efforts to build Hindu-Muslim unity, to create a nationalist mass consciousness that accepted justice, equality and fraternity as central objectives of nation-making.

Not only the British but also Indian feudal forces were taken aback by the scale and diversity of the Revolt. VD Savarkar was among those uncomfortable ones. His much-celebrated book on the Revolt of 1857 downplayed its mass character, overlooked the peasant and Adivasi rebellions it gave birth to, and portrayed Hindu-Mulsim unity as a tactical rather than principled move by the rebels.

Given that Savarkar’s worshippers are now ruling the country, no wonder their aggressive nationalism has little space for the Revolt of 1857 except its manipulative commemoration by VD Savarkar. Unwilling to accept a deeply plural and diverse popular movement as a foundational moment of the modern Indian nation, Hindutva narratives of the nation’s origin hark back to an ancient “Hindu” Brahminical past. It becomes important for today’s secular, democratic forces to commemorate the Revolt of 1857 as not only a war of independence but also as a foundational act of nation-making.