What India Must Learn From These Experiences

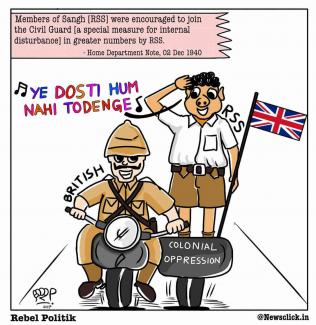

The RSS and the entire Hindu-supremacist faction in India remained aloof from India’s freedom struggle, instead choosing to collaborate with the colonial British rule’s “Divide and Rule” mission by breaking the unity of the people on Hindu-Muslim lines.

That Divide and Rule policy resulted in the bloody partition and the creation of India and Pakistan. Bangladesh broke from Pakistan later.

Now the Modi regime – implementing an RSS agenda – has announced that 14 August (Pakistan Independence Day) will be observed in India as “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day”. This is a move intended to perpetuate the divisive tragedy of partition inside India and between India and Pakistan.

Why does the Modi regime wish to reduce 74 years of India’s freedom to the blood-soaked chapter of Partition (in which on both sides of the border, Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs participated in mass killings and rapes)? How is it seeking to rewrite the history India’s freedom struggle, inserting the RSS and Hindu-supremacists into the story where they never had a part?

RSS’ is a Hindu-supremacist ideology and project, which dreams of turning India into a nation free of Opposition politics, where the RSS rules in the name of Hindus, and non-Hindus have to live as second-class citizens or as non-citizens. This vision of India goes against the entire spirit of the freedom struggle. Indians of all communities fought and sacrificed equally for freedom, and so all communities have an equal claim over India.

Is Indian Nationalism distinct from the European model of nationalism because it is “cultural” rather than “economic”?

This self-serving claim by RSS leaders could not be more false.

The nation state emerged in Europe as an “imagined” identity with the emergence of capitalism to fulfil capitalism’s historical needs – for creating a unified home market for capitalism, and as a binding force for new form of governance by replacing the ‘loyalty’ to a monarch by ‘loyalty’ to a ‘nation-state’. Language, religion were among the factors invoked as bases for nationalism. So the economic and political aspirations of emergent capitalism constituted the essence of nationalism in this first phase in the 16th-18th centuries.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a new phase of nationalism emerged: as a battle cry that united diverse people in colonised countries for liberation from the colonial subjugation of first generation of capitalist nations. So, anti-imperialism and the quest for sovereignty are the essence of nationalism in colonised countries this phase. Indian nationalism was not based on a unifying sense of shared religious beliefs, but a shared purpose of fighting the colonial oppressor.

Indian nationalism: Born Fighting Company Raj, Not Mughal Raj

India’s first war of independence in 1857 against Company Raj (the rule of the British East India Company) marks the first expressions of anti-colonial nationalism and a sense of belonging to one country. Following close on the heels of the great santhal hool led by Sido and Kanhu, the ‘peasants in uniform’ rose above religious narrow-mindedness and challenged the British Raj as Indians, as ‘Hindostanis’ in the sense of being legitimate owners of Hindostan: “Ham hain iske malik, Hindostan hamara” (We are its owner, Hindustan is ours)— in the words of the 1857 Anthem penned by Azimullah Khan. 1857 – with its diverse set of fighters hailing not only from princely feudal backgrounds, but also from the oppressed castes and women, thus announced the birth of popular, militant anti-imperialism some thirty years ahead of the birth of the Indian National Congress.

Prior to 1857 there had been a host of peasant and tribal uprisings against British rule. 1857 was the first such uprising that began to speak the language of belonging to one country – Hindustan – and defending it from the “firangi” (foreigner) who came to plunder it.

The British were frustrated at the firm unity among diverse communities displayed in the 1857 uprising: a senior British officer Thomas Lowe observed: “the cow-killer and the cow-worshipper, the pig-hater and the pig-eater, the cries of Allah is God and Mohammad his prophet and the mumbler of the mysteries of Brahma, they are all joined together in the cause.”

The command of the revolutionary army was in the hands of Bakht Khan, Sirdhari Lal, Ghaus Mohammed and Heera Singh – Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs all together. The artillery commander in Rani Lakshmi Bai’s army was Ghulam Ghaus Khan, and her infantry commander, Khuda Bakhsh. Her personal security officer who fought and died alongside her was Mundar – a Muslim woman.

There are any number of examples of Hindu-Muslim unity and sacrifice from 1857. After the brutal suppression of the uprising, the British formulated their “Divide and Rule” policy, which was especially venomous against the Muslim community.

Battle Between Rulers – Or Religions?

The RSS narrative claims that Mughal rule was “foreign” to India and resented and resisted by Hindus. So Indian nationalism, they claim, was Hindu in character since primordial times and must remain so now. RSS ideologue Golwalkar was keen to supplant anti-colonial nationalism with a Hindu “nationalism” that was hateful towards Muslims. He had written: “Anti-Britishism was equated with patriotism and nationalism. This reactionary view has had disastrous effects upon the entire course of the freedom struggle, its leaders and the common people.” (Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts)

And no wonder that this RSS narrative is as “Britishist” as it can get. It was James Mill who periodised Indian history into “Hindu Period, Muslim Period and British period”. When Yogi Adityanath, the CM of Uttar Pradesh says that “remembering Mughals is a symbol of slave mentality” he is actually echoing a colonial lie.

Even the historian RC Majumdar who follows Mill’s classification and shares a Hindu-nationalist ideology with the RSS, admits that an idea of “India” or Bharat as a nation “had no application to actual politics till the sixties or the seventies of the nineteenth century.” So the “Hindu” rulers and soldiers were not champions of “India”, and Muslim rulers and soldiers were not “invaders” or “occupiers”.

The facts show us that battles of the Mughal period were battles between rulers not religions; between kings not communities.

Take a few examples.

At the Battle of Haldighati in 1576, Akbar’s forces were led by his commander-in-chief, Man Singh I of Amber – a Hindu. They clashed with Maharana Pratap’s army which was led by a Muslim named Hakim Khan Sur.

What about Shivaji’s defeat of Afzal Khan? We hear the story that Shivaji was going to meet Khan without any weapons, but his bodyguard persuaded him to carry the famous ‘iron claws’ which he used to kill Khan when the latter attacked. Who was the bodyguard? Rustam Zawan – a Muslim. After Shivaji killed Khan, Khan’s assistant, Krishnaji Bhaskar Kulkarni, a Hindu, tried to kill Shivaji to avenge his master’s death.

The third example is that of Tipu Sultan the ruler of Mysore in the 1700s against the Maratha Army that the British had recruited against Tipu. After the ‘Hindu’ Maratha army ransacked the Sringeri monastery in Mysore at the behest of the British, Tipu Sultan offered his resources for the consecration of the Goddess, and sent gifts for the idol. A Hindu army destroyed a temple, and a Muslim ruler sent money and resources to rebuild it.

Indian nationalism was born against colonial oppression and plunder – against Company Raj not Mughal Raj, and was defined by the unity of diverse religious and caste communities.

Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s assessment of Mughal rule is worth remembering for its accuracy: “With the advent of the Mohammedans, a new synthesis was gradually worked out. Though they did not accept the religion of the Hindus, they made India their home and shared in the common social life of the people – their joys and their sorrows. Through mutual co-operation, a new art and a new culture was (sic) evolved ….”

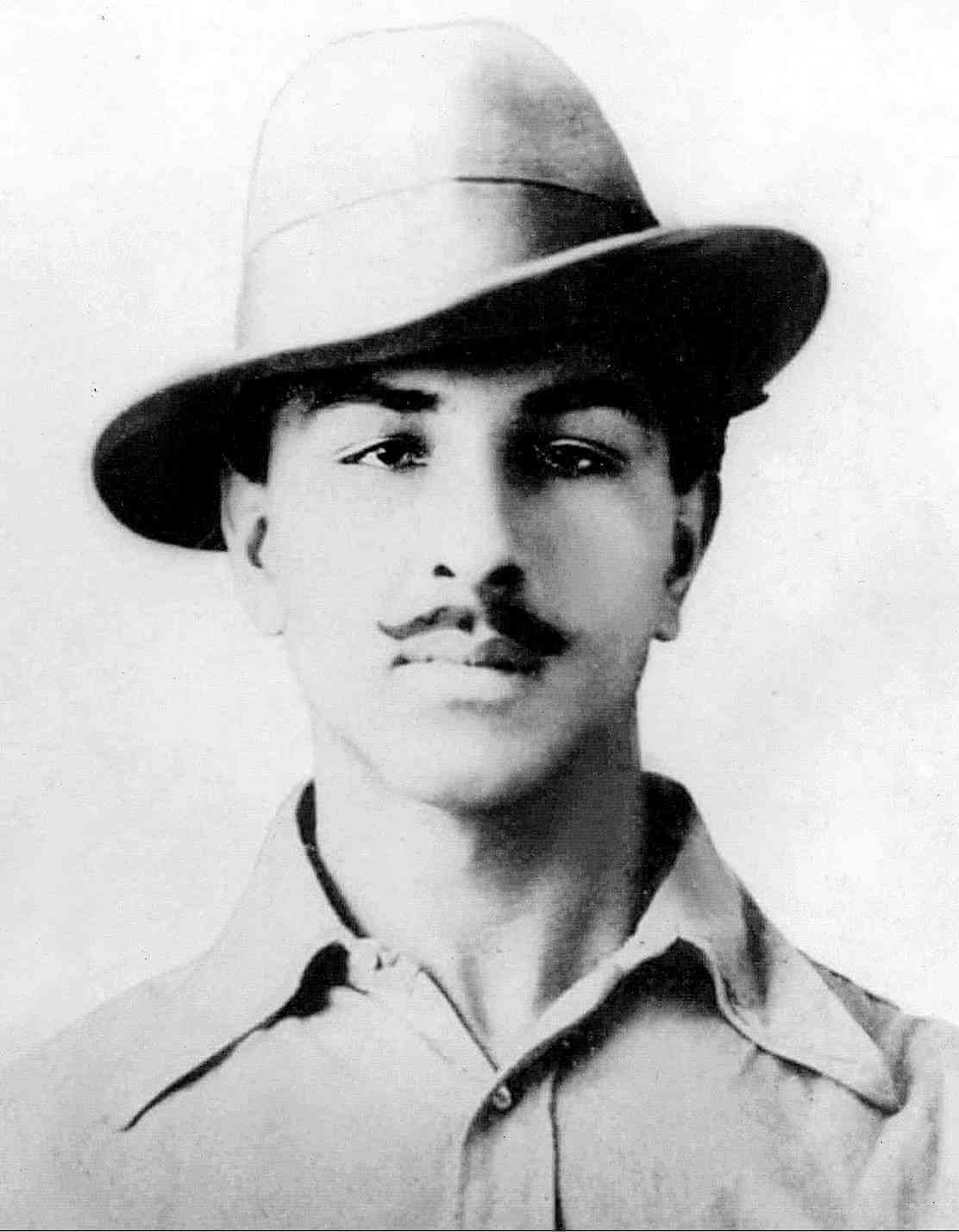

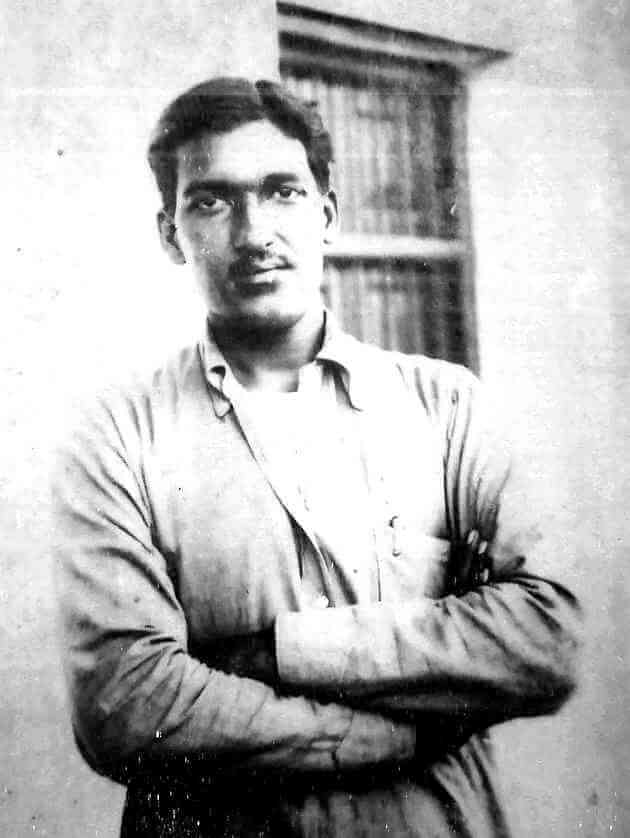

Bhagat Singh vs Savarkar; Sacrifice Vs Surrender

The RSS ideologue Golwalkar in a chapter titled ‘Martyr, Great But Not Ideal’ in his book Bunch Of Thoughts, expressed contempt for the martyrs of India’s freedom struggle, calling them “failures”. He wrote that “such persons are not held up as ideals in our society. We have not looked upon their martyrdom as the highest point of greatness to which men should aspire. For, after all, they failed in achieving their ideal, and failure implies some fatal flaw in them.” And he advised Indians that the willingness to sacrifice one’s life for the cause of the country’s freedom was not in the “complete national interest.”

Nor was Golwalkar’s attitude towards freedom fighters and martyrs an aberration – it was the norm among the Hindu-supremacist ideologues. The attitude of Hindutva ideologue Savarkar in the face of a life sentence contrasted with that of the revolutionary Bhagat Singh in the face of a death sentence tells us a lot.

Savarkar, imprisoned in the Cellular Jail in the Andamans in 1911, first petitioned the British for early release within months of beginning his 50 year sentence. Then again in 1913 and several times till he was finally transferred to a mainland prison in 1921 before his final release in 1924. His petitions begged the British rulers to let him go in exchange for his loyalty. He promised not only to give up the fight for independence but to work to persuade “misled” young freedom fighters back towards loyalty to the British. While inside jail he also complained that he was not given “better food” and “special treatment” compared to “ordinary prisoners” even though he was categorised as a “D” category prisoner. . He declared, “I for one cannot but be the staunchest advocate of constitutional progress and loyalty to the English government which is the foremost condition of that progress.”

In contrast, Bhagat Singh and his comrades on death row for “waging war” on the colonial state, declared boldly “Let us declare that the state of war does exist and shall exist so long as the Indian toiling masses and the natural resources are being exploited by a handful of parasites.” Moreover they demanded that as they were war prisoners, they must be treated as “war prisoners” and thus “we claim to be shot dead instead of to be hanged.” They concluded, “We request and hope that you will very kindly order the military department to send its detachment to perform our execution.”

Pro-British RSS Vs Ideologically Diverse Freedom Fighters

It is widely documented that RSS and Hindu Mahasabha did not participate in the freedom struggle and actively collaborated with the British. The RSS and BJP leaders now attempt to slyly “insert” RSS into the freedom struggle canvas.

One such attempt is a recent piece by RSS representative Rakesh Sinha. In an article published in Indian Express on August 15, 2021, he starts, strangely, with a warning against “the exaggerated glorification of the icons and incidents from the freedom struggle” during the celebrations of the 75th year of Indian independence. Who in fact are these icons and incidents whose “exaggerated glorification” Sinha resents? Knowing the Sangh’s record, including its past hatred for Gandhi and current hatred for Nehru, one can easily guess.

Rakesh Sinha argues that there were many differences among freedom fighters – about violent and non-violent tactics or the use of religious symbolism and imagery in the movement. That is a point many have made before him.

India’s March lo Freedom: The Other Dimension, authored Dipankar Bhattacharya and published by the CPIML in July 1997, for instance, traces the lessw observes that “If the ordinary people, workers and peasants, figure in this story of how India won her freedom, they do so only as numbers. Faceless, nameless numbers. ...But they are never shown in action as men and women fighting their own battle with their own vision, dynamism and initiative and trying to become arbiters of their own collective destiny. The working people are thus not only denied their due in the present. They are also denied their role in the past.”

But Rakesh Sinha’s claim that the RSS too was some kind of contrarian stream within the freedom movement, which has been hitherto neglected, is bogus. He writes that “forces like the Forward Bloc and the Indian National Army (INA), both formed by Subhas Chandra Bose, and the RSS, along with the revolutionaries, despite their differences in socio-economic perspectives, campaigned and acted to dethrone the British regime and made violence moral. At the same time, there was counter indoctrination of the masses against their ideology and programmes by the mainstream leadership.” So Sinha tries to slip RSS past our eyes, quietly and without any citations, in the company of those forces like Bose’ INA and Forward Bloc, and Bhagat Singh’s HSRA, as proponents of “violence” as opposed to the mainstream ideology of “non-violence.” This is thoroughly laughable, since the RSS’ only displays of violence were against the Muslims, never against the British! Never did an RSS leader advocate dethroning the British; instead they dissed “anti-Britishism” and advocated anti-Muslim hate and violence instead. And Bose and Bhagat Singh were one with Gandhi and Nehru and Azad on one thing – the absolute, forthright, unequivocal rejection of Hindu-supremacist nationalism and communal politics.

Violence/Non-Violence is in fact a jaded and outdated way of classifying the diverse actors of the freedom struggle. Studying their specific ideological inspirations and their strategies makes more sense than this lazy labelling. And the fault line that matters is not whether they advocated “violence” or “non-violence” – it is whether or not they rejected communal, Hindu-supremacist “nationalism”, and to what extent. There, Bose and Bhagat Singh stand alongside Gandhi and Nehru and Maulana Azad, uncompromisingly secular, with the likes of Tilak and Lajpat Rai flirting with Hindu supremacist ideologies without however giving up their determination to resist British rule. The RSS is quite distinct in its collaboration with the British and its never-flinching anti-Muslim hatred. That is why RSS is the proverbial stone in the lentils – it may hide but even if your eyes miss it, your teeth cannot let you swallow it unnoticed. It is quite indigestible.

The 1920s

In the 1921 Ahmedabad Session of Congress, Maulana Hasrat Mohani was the first to introduce a resolution for Purna Swaraj – complete independence. Gandhi and the Congress as a whole did not come to endorse this demand till 1929.

What other significant developments happened in the decade of the 1920s? The Communist Party of India and the RSS both came into being in 1925.

The CPI came into being on the heels of a spurt of working class struggles and emergence of four early communist groups in 1922-23. The enormous galvanising impact of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and the immediate factor of Gandhi’s controversial decision to call back the Non Cooperation movement in the wake of the Chauri Chaura incident, together formed the backdrop to the rise of the communist movement.

To quote Arindam Sen from his popular primer on the role of communists in the freedom struggle:

That the British rulers recognised communists as their most dangerous enemies was evident from a series of conspiracy cases - Peshawar , Kanpur , Meerut and others - hatched against them during 1920s and early 1930s. The most famous was the last named. Panicked at the high tide in workers’ struggles, rapid spread of WPPs, (see below) the revival of mass anti- imperialist movement provoked by the Simon Commission, the revolutionary activities of Bhagat Singh and his comrades, and the coming closer of communists and a section of the nationalist leadership, the government struck back in 1929 with a chain of repressive measures. Most important among these were: the Meerut conspiracy case, the Public Safety Bill and Trade Disputes Bill, and the prosecution of and death sentences to Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru. In March 1929, 31 labour leaders (including 3 Englishmen) from Calcutta , Bombay , and other parts of the country were rounded up. They were brought to Meerut for the conspiracy case. The accused communists made very good use of the courtroom for the spread of their ideology, aims and objectives. The British move to drive a wedge between communists and nationalist leaders also proved futile. Nehru, Gandhi and many others visited the Meerut jail while the accused communists also sent messages to the satyagrahis in different jails supporting their just struggles for political status. From the dock communists vigorously exposed the bankruptcy and hypocrisy of British rule in India and their ‘civilised’ legal system. Not only did workers all over the world launch agitations against the trial and conviction, even men like Romain Rolland and Prof. Albert Einstein raised their voices in protest against the trial.

In contrast to those within Congress pushing for Purna Swaraj, and the communists and other revolutionaries pushing for liberation from colonial rule as well as socio-economic transformation, the RSS has nothing whatsoever to show in terms of participation in the freedom struggle.

Ashfaqullah’s Warning

The Kakori Martyrs – Ramprasad Bismil, Ashfaqullah Khan, Rajender Lahiri and Roshan Singh – were deeply distressed while on death row by the attempts to spread communal poison by the “Shuddhi” movement run by Hindus to “purify” Muslims and reconvert them to Hinduism, and the “Tableegh” movement to propagate Islam in competition with Shuddhi. Three days prior to his hanging on December 19, 1927, Ashfaq’s last letter was smuggled out of Faizabad prison. In that letter, he appealed to Hindus and Muslims, “Live harmoniously and be united. Otherwise, you will be responsible for the plight of the country and you will be held responsible for the slavery of India.” He penned a couplet: “Yeh jhagre aur bakhere metkar aa-pass mein mil jaao/Abas tafreeq hai tum-me ye Hindu aur Musalman ki” – Leave these quarrels behind, close your ranks/Strange are your distinctions of Hindu and Muslim”.

Netaji Set Up Armed Resistance While Hindu Mahasabha Recruited for British Army

It is well known that Netaji Bose set up the Azad Hind Fauj to offer an armed challenge to the British colonial rule. While Bose can be criticised for allying with Japan and fascist Germany, it is undeniable that he was secular. In ‘Free India and Her Problems’, Boase wrote that it was the British who had set Hindus against Muslims, and that communal tension would go when the British went. He envisioned a state where “religious and cultural freedom for individuals and group” should be guaranteed and no “state-religion” would be adopted. The trial of the Azad Hind Fauj leaders Shah Nawaz Khan, Prem Sahgal and Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon, Abdul Rashid, Shinghara Singh, Fateh Khan and Captain Malik Munawar Khan Awan itself proved to be a great inspiration for anti-colonial unity and a rebuff to communal politics.

In contrast, Savarkar as Hindu Mahasabha President recruited for the British Army during World War II:

“So far as India’s defence is concerned, Hindudom must ally unhesitatingly, in a spirit of responsive co-operation, with the war effort of the Indian government in so far as it is consistent with the Hindu interests, by joining the Army, Navy and the Aerial forces in as large a number as possible and by securing an entry into all ordnance, ammunition and war craft factories…Hindu Mahasabhaites must, therefore, rouse Hindus especially in the provinces of Bengal and Assam as effectively as possible to enter the military forces of all arms without losing a single minute.” (V.D. Savarkar, Samagra Savarkar Wangmaya: Hindu Rashtra Darshan, vol. 6, Maharashtra Prantik Hindusabha, Poona, 1963, p. 460.)

Another Hindu Mahasbha bigot and current Sangh hero Syama Prasad Mookerjee was the Finance Minister of Bengal and the second most senior minister in the government after Bengal’s Prime Minister, Fazlul Haq from the Muslim League. Both the League and Mahasabha – fierce rivals playing communal politics – participated in the British war effort. When Congress elected representatives resigned in support of the Quit India movement, HM and ML refused to resign. Mookerjee on July 26, 1942, wrote to the British governor of Bengal, John Herbert, promised to act sternly against “Anybody who, during the war, plans to stir up mass feelings, resulting in internal disturbances or insecurity, must be resisted by any government that may function for the time being.”

RSS Denigrated The Indian Tricolour:

The Same Day A Muslim Couple Designed The National Flag

On 14 August 1947, the RSS English organ Organiser denigrated the national tricolour in the following words: “The people who have come to power by the kick of fate may give in our hands the Tricolour but it will never be respected and owned by Hindus. The word three is in itself an evil, and a flag having three colours will certainly produce a very bad psychological effect and is injurious to a country.”

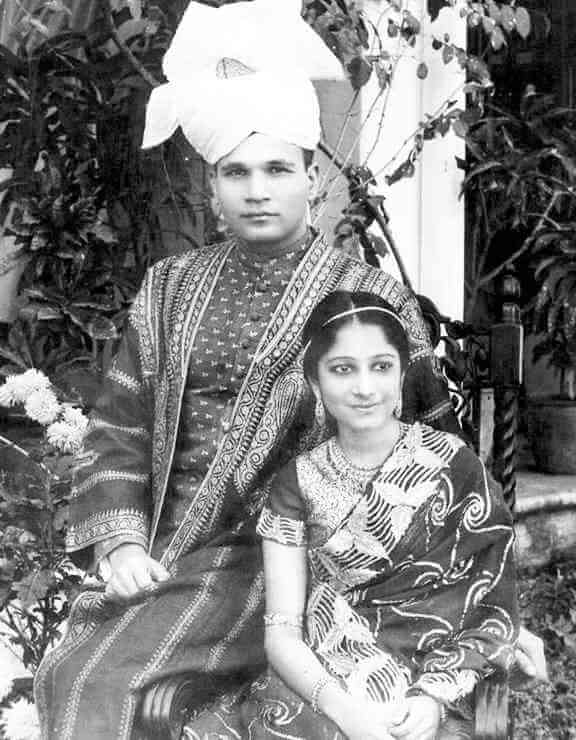

An extremely interesting story lies behind the designing of the national tricolour on the same day, the eve of independence, by 28-year-old Surayya Tyabji and her husband Badruddin Tyabji.

Their daughter Laila Tyabji writes that a couple of months before independence, at Nehru’s request, her father Badruddin Tyabji “set up a Flag Committee headed by Rajendra Prasad, and sent letters to all the art schools asking them to prepare designs. Hundreds came in, all quite ghastly. Most of them heavily influenced by the British national emblem, except that elephants and tigers, or deer and swans replaced the lion and unicorn on either side of the British crown. The crown itself was replaced by a lotus or kalash or something similar.” As Nehru and everyone for desperate and time flew by, her “parents had this brainwave of the lions and chakra on top of the Ashoka column. (They both loved the sculpture and ethos of that period). So, my mother drew a graphic version and the printing press at the Viceregal Lodge (now Rashtrapati Niwas) made some impressions and everyone loved it. Of course, the four lions (Lion Capital of Ashoka) have been our emblem ever since.”

It was then that Surayya and Badruddin together came up with the design for what is today India’s flag: modifying Pingali Venkayya’s design of the Congress tricolour flag, replacing the charkha with the same Ashoka chakra.

Laila writes, “My father watched that first flag – sewn under my mother’s supervision by Edde Tailors & Drapers in Connaught Place – go up over Raisina Hill.” This loving personal involvement and attention to detail is what makes the national tricolour special. In Laila’s words, “Despite the scars of Partition, there was a unity and sharing. The struggle for freedom had bound very diverse people together. People connected then to a broader identity – Indianness rather than caste or community.”

Who Broached Partition, and Who Resisted It?

Modi had declared 14 August as Partition Horrors Remembrance Day in a blatant attempt to blame Pakistan and Muslim for “partition horrors” and incite a hateful urge amongst Hindus to reenact those horrors on Muslims today. Evidence of these hateful preparations can be seen in the manner in which large rallies are being allowed in Haryana and Delhi unchecked, in which leaders of BJP and allied radical Hindu-supremacist outfits call for genocide of Muslims; and Hindu-supremacist online gangs “auction” Muslim women journalists online.

In the wake of partition and independence, the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha stoked hatred towards Gandhi, blaming him for partition – it is this hatred that radicalised Godse and led him to shoot Gandhi dead. Now under Modi, Gandhi is reduced to an icon for “Swacch” toilets, and it is Nehru who is hated and vilified for partition, falsely claiming that Patel was not in favour of partition. In fact, it was Patel who first agreed to Mountbatten’s proposal of Partition.

Savarkar Mooted Two Nation Theory Before Jinnah Did

In his presidential address at the All India Hindu Mahasabha convention in Karnavati (Ahmedabad) in 1937, Savarkar declared, “India cannot be assumed today to be a unitarian and homogeneous nation, but on the contrary there are two nations in the main; the Hindus and the Moslems, in India.” (Samagra Savarkar Vadmay- Volume 6, Maharashtra Prantik Hindusabha Publication, 1963-65, Page 296)

Jinnah mooted Pakistan and the Two-Nation Theory only in 1940.

Syama Prasad Mookerjee Campaigned For Partition

As Professor Shamsul Islam establishes, “In reality, Mookerjee supported Partition right from 1944, and was once even shouted down at a Calcutta rally for advocating splitting Bengal. On May 2, 1947, Mookerjee even wrote secretly to Viceroy Louis Mountbatten asking for Bengal to be partitioned even if India remained united. Mookerjee would also vehemently oppose plans for a united, independent Bengal being pushed by the Prime Minister of Bengal, Hussain Suhrawardy, and the two major Congress leaders in Bengal, Sarat Chandra Bose (older brother of Subhash Chandra Bose) and Kiran Sankar Roy. Mookerjee preferred a communal Partition as per the two-nation theory instead.”

Muslims Against Partition

While the Hindu Mahasabha and Muslim League drove a wedge between Hindu and Muslim communities, there were many prominent progressive Muslims who passionately campaigned against the Partition proposal.

Foremost among them was Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, who tried in vain to persuade Patel not to accept the proposal. In India Wins Freedom Azad wrote, “I was also convinced that if the Constitution for free India was framed on this basis and worked honestly for some time, communal doubts and misgivings would soon disappear. The real problems of the country were economic, not communal. The differences related to classes, not to groups. Once the country became free, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs would all realise the real nature of the problems that faced them and communal differences would be resolved. found that Patel was so much in favour of partition that he was hardly prepared even to listen to any other point of view. For over two hours I argued with him. I pointed out that if we accepted partition, we could create a permanent problem for India. Partition would not solve the communal problem but would make it a permanent feature of the country.”

How prescient Maulana Azad was – the RSS, BJP and Modi regime now do indeed seek to make Partition a permanent wound. The foreboding expressed by Azad on July 17 1946 is today dangerously close to coming true: “Muslims would awaken overnight and discover that they have become aliens and foreigners, backward industrially, educationally and economically; they will be left to the mercies of what would become an unadulterated Hindu Raj.”

Allah Baksh:

“Put Communalists In A Cage”

At the historic All India Independent (Azad) Muslims Conference which began on April 27 1940 in Delhi, newspapers recorded a gathering of not less than 75000 Muslims. Allah Baksh, a prominent leader from Sind, inspired the gathering to reject the Muslim League proposal of Partition. He told a reporter that day, “It is better to put the communalists in a cage so that they may not spread the hymn of hatred between the Hindus and the Muslims.”

Communalists “Only Say Nice Things To Our Rulers”

The great Shibli Nomani, founder of the Shibli College at Azamgarh, was a dedicated campaigner for a united India, exposing the politics of the Muslim League. In a poem titled ‘Muslim League’, he satirised the party thus:

It is patronised by the government and popular with the rich

It is the patron of the community - and subservient to the rulers

I asked the League to tell the rulers of our plight

About police high-handedness and court cases

About the sorrow-filled life of the peasants

After listening, League said -

It is my nature to say only nice things to the rulers.

The selfsame could well have been said of the Hindu Mahasabha and RSS!

Urdu Poetry Against Partition

A host of poems were written in Urdu by Muslims, appealing to Hindus and Muslims against Partition. Shamim Karhani’s ‘To those who want Pakistan’ asked, “Tell me what does ‘Pakistan’ (land of the holy) mean? Is this land, where we Muslims are, unholy?”

Karhani’s ‘Indian Warriors’ called for a war against communal hatred: “Let the fights over cow and loudspeaker go to hell”. In “hamara Hindostan” Karhani declared “If someone asks the traveler where I’m from; I will proudly say it is Hindostan.”

Several of these poems have been collected by Shamsul Islam in his book Muslims Against Partition.

In the 75th year of India’s independence, it is important to collect the writings and documents from both sides of the border, which expressed the pain and anguish and guilt of Partition, so that the people of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh can vow to learn from Partition never to allow communal violence and discrimination and war-mongering to sully the subcontinent again.