This year we are observing the twenty-fifth death anniversary of Comrade Vinod Mishra. As we recall his historic contribution to the reorganisation, expansion and consolidation of the CPI(ML) in the post-Naxalbari phase and pay tribute to his ever-inspiring revolutionary legacy, it will be most pertinent to revisit his core ideas and contributions in the context of today's central challenge of foiling the fascist raid on India's constitutional democracy.

When the Party Central Committee was reorganised on July 28, 1974 two years after the martyrdom of Comrade Charu Mazumdar, the CPI(ML) was battling a severe setback across the country. Almost the entire central leadership of the newly formed party had either been killed or jailed by the state. Thousands of party activists had embraced martyrdom or were facing acute repression. The fledgling party organisation was ill equipped to face such a severe crackdown; and confusion, demoralisation and division in the movement and organisation became the order of the day. It was in this extremely challenging situation that Comrade VM had taken over the responsibility of leading the party after Comrade Jauhar's martyrdom on 29 November, 1975.

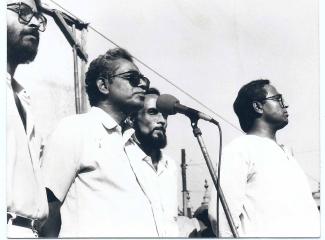

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD COMRADE VM POSTER

What were the key ideas or factors that drove the party's recovery and expansion in the late 1970s and 1980s amidst an upsurge of anti-feudal struggles and vibrant multifarious mass initiatives? A dialectical evaluation of the past and the development of a revolutionary tactical line on the basis of a serious study of Marxism-Leninism and writings of Mao, deep social investigation and analysis, and a critical engagement with the Indian polity from the standpoint and perspective of revolutionary social transformation - these were the two crucial factors propelling the party's trajectory of growth. Comrade VM paid keen attention to every aspect of this trajectory and the party took a series of bold political steps in response to the demands of a dynamic situation.

The Naxalbari uprising was not just a major milestone of the communist movement but a great turning point for modern India. One could see its impact in its immediate aftermath in the electrifying speed with which the CPI(ML) took shape and spread its wings, and the massive pull it generated not just among India's predominantly Dalit-Adivasi rural poor but even among the educated urban youth and intelligentsia. It became independent India's first major mass upsurge for radical transformation. The massive crackdown and setback created two opposite erroneous responses - one trend started disowning and maligning the upsurge in the name of rectification of mistakes while the other adopted a defensive approach of elevating the slogans and forms of struggle of the Naxalbari period to a level of strategic permanence and finality.

Under Comrade VM's leadership the reorganised CPI(ML) developed the dialectical approach of learning from mistakes and carrying forward the spirit and lessons of Naxalbari in changed conditions and circumstances. Once we succeeded in seeing Naxalbari in the context of a specific juncture, we could begin to address the challenge of extricating tactical questions from the strategic course or perspective. This was how the party moved on in cautious but bold and confident steps, imbibing the revolutionary spirit of Naxalbari and spreading it to the wider arena of mass initiatives. Charu Mazumdar's last words in which he urged keeping the party alive, forging close ties with the masses and upholding their interests as the supreme duty of the party, immensely helped this process of the party's recovery and reorganisation.

The formation of the CPI(ML) in the wake of the Naxalbari peasant upsurge was a crystallised expression of the rejection of economism and keeping politics in command. Immediate - often economic - demands are invariably central to the development of mass struggles, and communist politics which seeks to end human exploitation has to link up this mass work with the ideological and political challenge of motivating and mobilising the struggling forces to achieve the larger goal of changing the capitalist order. Herein lies the great challenge of combining the current task with the future goal. As the reorganised CPI(ML) started focusing on mobilising the people around their immediate demands, it paid special attention to linking up immediate demands and local struggles with the national vision of a democratic alternative. This was to lead to the emergence of the Indian People's Front as an all-India radical democratic platform.

The development of an all-India political platform unleashing a series of bold initiatives with a radical democratic vision lent a new impetus and dimension to the growth of local mass activism. The all-India political thrust served as a built-in counterweight against the common tendency of localism, keeping economism in check and politics in command. In the latter half of the 1980s when IPF decided to contest elections, it became a bitter struggle to secure the right to vote for the oppressed poor by resisting booth-capturing by feudal forces. The transition from election boycott to electoral participation meant a determined battle for the electoral assertion of the excluded and oppressed people, and in a state like Bihar it invited a tremendous feudal backlash. Serial massacres by private armies, killings of leaders and activists, and persecution of organisers by implicating them in false cases and subjecting them to prolonged incarceration - all-out attempts were made to stop the electoral assertion and advance of the revolutionary movement.

Under the leadership of Comrade VM the CPI(ML) withstood these challenges with great courage and determination and held high the banner of revolutionary democracy against all odds. The power of militant anti-feudal struggles of the people and multifarious democratic initiatives for social justice and transformation sustained and strengthened the party in the face of adverse conditions and concerted attacks by feudal-criminal forces. But the electoral emergence of the party in the then central Bihar (south Bihar after bifurcation of the state) in the late 1980s and early 1990s also strengthened the feudal reaction. The rise of the Hindutva brigade riding on the Ram Mandir campaign brought a palpable change in Bihar and the feudal violence against the fighting rural poor and their party CPI(ML) started acquiring vicious fascist overtones. After the Bathanitola massacre in Bhojpur, the first major carnage perpetrated by the infamous Ranvir Sena, Comrade VM detected unmistakable communal streaks in the Ranvir Sena's approach. Indeed, the violence against the women and children in Bathanitola was a precursor to the pogrom we witnessed in Gujarat in 2002.

Ever since Advani's rath yatra and its eventual culmination in the December 6 1992 demolition of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Comrade VM had been very clear about the fascist nature of the entire build-up. He never saw it as a clash between fundamentalism or fanaticism and liberalism, for him it was a clear battle between communal fascism and constitutional democracy. The threat to democracy had started aggravating with the simultaneous rise of Hindutva and corporate power, and Comrade VM paid close attention to this growing danger and did his best to sensitise and prepare the party for this new challenging phase. In the tenth year of the Modi government at the centre when we look back at the short-lived first NDA government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the late 1990s, it may look pretty mild, and many political observers were indeed misled by the manufactured 'moderate' image of Vajpayee and his government, but Comrade VM continued to forewarn us about the shape of things to come. His last days were totally focused on building an anti-fascist political campaign in India.

For Comrade VM, the focus on democracy was never a matter of compromise with the status quo but rather an essential aspect of social and political transformation. From the late 1980s onwards, Comrade VM highlighted the key lessons from the collapse of the Soviet model of socialism and drew our attention to the challenge of socialist regeneration through more participatory democracy and socialist economic dynamism. The collapse and disintegration of the Soviet Union also created a unipolar moment and US imperialism took full advantage of this juncture. From the 1990-91 Gulf War onwards, it forged a new US-led western alliance marked by ‘Clash of Civilisations’ anti-Muslim rhetoric which evolved into the global War on Terror. It is this alliance combined with the more recent wave of far-right global consolidation which is the bedrock of support for Israel today in its ongoing genocidal campaign in Gaza.

The disappearance of the Soviet bloc meant an aggressive expansion of global capitalism and a concerted campaign of liberalization, privatisation and globalisation, and Comrade VM saw within this expansion the seeds of new contradictions and deeper crisis. The multiple crises of global capitalism in the last two decades coupled with the havoc being created by climate change have borne him out. This has also led to a new crisis of liberal democracy and the welfare state and renewed rise of fascism on a global scale. Writing on the Communist Manifesto in the 150th year of its publication, Comrade VM highlighted the challenge of exploring forms of proletarian democracy transcending the limits of even the best forms of bourgeois democracy so that the defeat of capitalism in future is seen not just as victory of socialism but also democracy.

At the time of adoption of the Constitution of India and the introduction of parliamentary democracy, Babasaheb Ambedkar had warned us about the contradictions and limits of the new system - the contradiction between mere equality of vote and deeply entrenched social and economic inequality, and the clash between India's traditional undemocratic soil and the top-dressing of democracy applied from above through constitution. In their own contexts, Ambedkar the radical democrat and VM the revolutionary communist addressed the same anomalies and contradictions within India's society and polity and sought ways to promote the assertion and expand the rights of the oppressed and marginalised people. Ambedkar was initially hopeful of reconciling socialist economics and parliamentary democracy; while VM, though never under any illusion of finding a parliamentary path to socialism, was committed to using and expanding the potential of whatever democracy was available to advance the forward march of the Indian people. Today when parliamentary democracy in India is facing a serious fascist offensive with a growing clamour for a new constitution or at any rate for a complete subversion of the existing constitution and the institutional architecture of parliamentary democracy, the ideas and contributions of Comrade VM remain an inspiring guide in India's battle to defeat fascism and secure a robust democratic future.