(A version of this article first appeared in The Leaflet.)

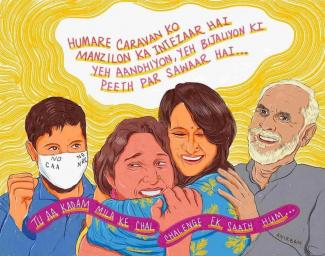

The Delhi High Court ordered the release of three of the student activists charged under UAPA in the Delhi riots cases - Asif Iqbal Tanha, Natasha Narwal, and Devangana Kalita. These three had secured bail in other Delhi riots FIRs, but were still in prison thanks to being charged under UAPA. The mood outside Tihar jail when these three came out of prison was charged with emotion. Most felt was the absence of Mahavir Narwal, Natasha’s father who fell victim to Covid-19 before he could see his daughter free. The slogans painted onto Asif’s face mask (defiantly saying No to CAA-NPR-NRC), and the slogans raised by the three young voices, lit up a spark of hope, even as we knew that it might not be long before there would be attempts to slam shut the window opened up by the exemplary Delhi HC orders.

Sure enough, the very next day, a Supreme Court bench heard the appeal by the prosecution seeking to stay the Delhi HC orders. While the SC did not agree to stay the orders, and allowed the three students to remain out on bail, it fenced off the bail orders in a silo, ordering that these would not be allowed to serve as a precedent in other UAPA bail cases until a judgment was passed on the appeal. So for at least a month, pending a final judgment by the SC, other UAPA prisoners cannot benefit from the Delhi HC bail orders.

What do the Delhi HC orders say, and why are they significant? In fact, those orders should be read and discussed in every village, every jhuggi, every mohalla in India. Poor communities in India are intimately aware of the police forces’ habits of framing innocents, using torture to extract false confessions, and indulging in custodial brutality. But when the media acts as stenographer and propagandist for the police and their political bosses, and vilify individuals and entire minority communities (such as Muslims, Sikhs, and adivasis) as well as human rights activists, as “terrorists” the same communities rarely find the confidence to publicly cast doubt on the police and media cacophony. The Delhi HC orders, if understood, can equip Indians to better understand their own rights, and learn to assess allegations levelled by the police and the State, by the correct yardstick.

UAPA and Watali: Recipe For Indefinite Incarceration

For police forces all over India, the UAPA reinforced with the latest amendments, serves as the perfect tool to imprison dissenting voices for long, indefinite periods, without trial and with very little chance of bail.

How this works is that UAPA statutorily condemns an accused to pre-trial detention, since the police enjoys a period of 180 days to investigate the case (as opposed to the usual 60 to 90 days under CrPC), and moreover those accused under UAPA are not entitled to bail if the Court is of the opinion that there are “reasonable grounds for believing that the accusation against the person is prime facie true”. The latter flows from the Supreme Court judgment in the Watali case (National Investigation Agency vs. Zahoor Ahmad Shah Watali).

This meant that the Court hearing a bail application could hear only the prosecution side, and was obliged to accept the prosecution allegations on their face, while being legally restrained from hearing any defence offered by the accused. So even if an allegation of “terrorism” under UAPA was based on a piece of forged “evidence”, the Court hearing a bail application by the accused, could not consider whether or not the evidence was forged. The Court could only examine whether the allegations appeared to be “true on the face of it,” without looking beyond the “face of it.”

In effect, this has meant that UAPA prisoners have been detained for years without bail, as the investigative agency delays trial on the pretext of continued investigation. In the Bhima Koregaon case, and the Delhi riots case, as well as several cases involving unarmed protestors all over India, we have seen how the UAPA is used to criminalise protest and punish protestors.

The Delhi High Court orders giving bail to three students booked under UAPA in the Delhi riots cases, have finally clarified the issues and asserted the constitutional principles that need to be upheld in bail hearing in all matters including UAPA matters. In ordering their release on bail, those orders have moreover exposed the hollowness and vindictiveness of the whole Delhi Police investigation in the riots.

Delhi HC’s Answer To Watali

The Delhi HC interpreted what is arguably one of the UAPA’s worst aspects, in favour of the constitutional rights of the accused. In the bail order for Asif Iqbal Tanha, it points out that the TADA and POTA laws had required courts to find accused persons prima facie “not guilty” in order to grant bail. The UAPA, in contrast, prevents courts from “delving into the merits or demerits of the evidence at the stage of deciding a bail plea” (as interpreted in Watali), and to restrict themselves to judging whether the allegations against the accused are “prima facie” reasonable or not. Here, instead of interpreting this to mean that the court must blindly accept the allegations of the prosecution as “prima facie true”, the Delhi HC applies its mind to judge whether or not those allegations reasonably deem UAPA charges or not. The Delhi HC says that just as the court is prevented at the stage of bail, from looking into evidence that may prove the accused “not guilty”, it is equally expected to refrain from looking at anything but the bare allegations of the prosecution. The court cannot look at any inferences that the prosecution seeks to draw on the basis of evidence it claims to have. And the Delhi HC finds that the chargesheets against Asif, Natasha and Devangana, only accuse them of belonging to WhatsApp groups, or arranging a sim card to one of the administrators of one such WhatsApp group, planning protests against the CAA law, encouraging people to join the protests, and so on. And these, the Delhi HC concludes, simply do not meet any reasonable definition of a “terrorist” act for which the UAPA is meant.

The Delhi HC is quite scathing about the Delhi Police’s attempt to compensate for the lack of specific and reasonable allegations, with words meant to shock and awe. It says that “the mere use of alarming and hyperbolic verbiage in the subject charge-sheet” cannot make up for the “complete lack of any specific, particularised, factual allegations, that is to say allegations other than those sought to be spun by mere grandiloquence”.

What about allegations that the chakkajam (blockade of roads and highways) turned violent? There, again, the Delhi HC makes the most reasonable observation: that the ordinary penal laws (under which the accused have already been charged, have secured bail, and are awaiting trial) are more than enough to deal with such offences. “Wanton use of serious penal provisions would only trivialise them”, says the Delhi HC in the bail order for Asif.

The Najeeb Bail Order: No To Indefinite Imprisonment

The Delhi HC recalls the Supreme Court judgmjent upholding the Kerala HC judgment giving bail in the KA Najeeb case. The ASG representing the prosecution argued that the Najeeb order was given on the grounds that accused had already been incarcerated for a very long time and there was no likelihood of the trial being completed in a reasonable time. This was not (yet) the case with the Delhi riots accused, argued the ASG. In response, the Delhi HC asked: “Should this court then wait until the appellant has languished in prison for a long enough time to be able to see that it will be impossible to complete the deposition of 740 prosecution witnesses in any foreseeable future, especially in view of the prevailing pandemic when all proceedings in the trial are effectively stalled? Should this court wait till the appellant’s right to a speedy trial guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution is fully and completely negated, before it steps in and wakes-up to such violation? We hardly think that that would be the desirable course of action. In our view the court must exercise foresight and see that trial in the subject charge- sheet will not see conclusion for many-many years to come; which warrants, nay invites, the application of the principles laid down by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in K. A. Najeeb (supra).”

Process As Punishment

Two years ago, Mohammed Irfan Gaus (then 31), under-trial in a UAPA case, got bail in Bombay HC on the same grounds that Asif, Natasha and Devangana did: no prima facie evidence was found to merit UAPA charges. Gaus, and another UAPA accused in the same case, Ilyas, had by then spent seven years in Taloja jail (the same jail where the Bhima Koregaon UAPA prisoners are now incarcerated.) The Supreme Court stayed the bail order for Gaus.

On June 15, 2021 – the same date that the Delhi HC issued its bail orders - Gaus and Ilyas were acquitted by a special UAPA court. There was absolutely no evidence against them. But these innocent men had spent nine years – close to a decade of their young lives - in prison. This is what UAPA is for - to punish innocents whom the Government dislikes for their faith, or for their views.

By staying Gaus's bail the SC kept an innocent man in prison for 9 years instead of 7. But surely these men should have got bail immediately following arrest, if it was clear that the case was going to last "many-many years", in the words of the Delhi HC? To end this phenomenon of "due process" becoming a punishment for innocent under-trials, the spirit of the Delhi HC orders must be upheld, to ensure that bail is given promptly as a rule, with only the rarest of rare exceptions.

The Delhi HC orders are a reminder of how unjust our "due processes of law" have become - for the poor under all laws because they cannot afford bail, and for everyone charged under UAPA. “Due process”, which under UAPA means years of imprisonment based on no evidence could be a death sentence for under-trials today because they could get Covid or black fungus. For elderly/ill prisoners like Stan Swamy, Varavara Rao, Gautam Navlakha, Anand Teltumbde, they could die in prison though innocent.

There is also a glaring communal and political double standard. Mohammed Ilyas and Mohammed Irfan Gaus were arrested on the basis of false confessions extracted under torture, and imprisoned for nearly a decade. Adivasis imprisoned under UAPA, falsely accused of being “Maoists” likewise spend years in prison as under-trials. But Sadhvi Pragya, credibly charged for her role in an act of Hindu-supremacist terrorism, is given bail, fielded as an MP candidate by the Prime Minister himself, and wins the election. In her defence, the BJP trots out all the human rights talk (she is not guilty till convicted, she was tortured in custody, she was falsely framed, etc) that they deride when it is applied to other accused persons.

A Threat To Democracy

In the bail order for Natasha and Devangana respectively, the Delhi HC uses very clear language to indicate that the Delhi Police chargesheets against these three accused persons pose a threat to democracy by seeking to criminalise protest.

In Natasha’s bail order, the court says: “We are constrained to express, that it seems, that in its anxiety to suppress dissent, in the mind of the State, the line between the constitutionally guaranteed right to protest and terrorist activity seems to be getting somewhat blurred. If this mindset gains traction, it would be a sad day for democracy.”

In Devangana’s bail order it says: ”We are afraid, that in our opinion, shorn-off the superfluous verbiage, hyperbole and the stretched inferences drawn from them by the prosecuting agency, the factual allegations made against the appellant do not prima facie disclose the commission of any offence under sections 15, 17 and/or 18 of the UAPA.

“We are constrained to say, that it appears, that in its anxiety to suppress dissent and in the morbid fear that matters may get out of hand, the State has blurred the line between the constitutionally guaranteed ‘right to protest’ and ‘terrorist activity’. If such blurring gains traction, democracy would be in peril.” (italics in original)

The Delhi HC bail orders vindicate what pro-democracy activists have been saying since last year: that the Delhi Police investigation is blatantly biased, and has spun a fantastic conspiracy theory to falsely accuse anti-CAA protestors, especially those of the minority Muslim community, of the very “riots” (in fact, planned and targeted violence) of which they were actually victims. The Delhi Police is yet to take any action at all against Kapil Mishra, Anurag Thakur and other BJP and RSS leaders who called upon mobs to shoot and kill protestors, and led violent, armed mobs on Delhi streets.

While every UAPA prisoner must get bail in keeping with the principles outlined in the Delhi HC order, that alone will not constitute justice. Justice demands that the whole Delhi Police investigation be scrapped and replaced by a fresh investigation monitored by the Delhi HC; that the Delhi Police officers responsible for imprisoning innocents on the basis of a chargesheet that has nothing but “superfluous verbiage”, be punished. Above all, each of the persons forced by the Delhi Police’s vindictiveness and political bias to be in prison in these pandemic times, must be adequately compensated.

|

The requirement of being satisfied that an accused is ‘not guilty’ under TADA or POTA meant that the court must have reasons to prima facie exclude guilt; whereas under UAPA the requirement of believing an accusation to be ‘prima facie true’ would mean that the court must have reason to prima facie accept guilt of the accused persons, even if on broad probabilities; The decision of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Watali (supra) proscribes the court from delving into the merits or demerits of the evidence at the stage of deciding a bail plea; and as a sequitur, for assessing the prima facie veracity of the accusations, the court would equally not delve into the suspicions and inferences that the prosecution may seek to draw from the evidence and other material placed with the subject charge-sheet. To bring its case within Chapter IV of the UAPA the State must therefore, without calling upon the court to draw inferences and conclusions, show that the accusations made against the appellant prima facie disclose the commission of a ‘terrorist act’ or a ‘conspiracy’ or an ‘act preparatory’ to the commission of a terrorist act. |