The Work Report is a rather curious sort of document to be adopted at a communist party congress. There is not a word on imperialism or the international situation – even the ongoing Russian aggression on Ukraine has not been mentioned, let alone condemned. It is a very long statement on the party’s assessment of the national situation, review of work and tasks ahead, yet the biggest challenge in national life – the Covid-19 outbreak – gets only a very brief mention. And that too in a vainglorious tone, calling it a successful “all-out people’s war to stop the spread of the virus”, when in reality Chinese citizens had already been suffering and protesting against the government’s rough-and-tough execution of the “Zero-Covid policy”.[1]

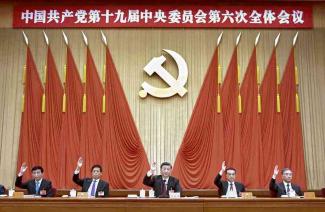

Particularly disturbing in this most important document presented by Xi Jinping on behalf of the Central Committee is the unseemly glorification of the GS-cum-President-cum-Chairman of the Central Military Commission.[2] It carries a bad omen of the rise of yet another super-leader above the collective leadership and monopolization of all power in his/her hands – a phenomenon that always proves catastrophic in the long run.

Now let us focus on the major political takeaways from the Congress. To base ourselves on solid evidence, we will be quoting extensively from the Work Report, adding our observations in-between and shorter comments or clarifications in square brackets. Unless stated otherwise, all emphases will be ours.

Backdrop to the 20th Congress

“A decade ago [when Xi took over as General Secretary] this was the situation we faced:

Inside the Party, there were many issues with respect to upholding the Party’s leadership, including a lack of clear understanding and effective action as well as a slide toward weak, hollow, and watered-down Party leadership in practice. … Privilege-seeking mindsets and practices posed a serious problem, and some deeply shocking cases of corruption had been uncovered. …

“China’s economy was beset by acute structural and institutional problems. …

Misguided patterns of thinking such as money worship, hedonism, egocentricity, and historical nihilism [negativism/scepticism] were common, and online discourse was rife with disorder. All this had a grave impact on people’s thinking and the public opinion environment.”

The serious problems, the Report tells us, have largely been resolved under the leadership of Xi:

“All Party members have become more purposeful in closely following the Party Central Committee in thinking, political stance, and action… We have accelerated efforts to build our self-reliance and strength in science and technology, with nationwide R&D spending rising from 1 trillion yuan to 2.8 trillion yuan, the second highest in the world. Our country is now home to the largest cohort of R&D personnel in the world. …”

Indeed, China’s rather unexpected pace of progress in frontier sciences and technologies and their application in contemporary sunrise industries such as semiconductors, state-of-the-art batteries, electric vehicles, electronic products etc. is something the West is in a tizzy about. Because it throws up a serious challenge to its technological, economic and thereby also political domination.

The achievements notwithstanding, the Report goes on to say, there are many unresolved problems and unfinished tasks:

“Quite a few challenges exist in the ideological domain. There are still wide gaps in development and income distribution between urban and rural areas and between regions. Our people face many difficulties in areas such as employment, education, medical services, childcare, elderly care, and housing. Ecological conservation and environmental protection remain a formidable task. … “Eradicating breeding grounds for corruption is still an arduous task. … in our fight against corruption … steps [must be taken] to ensure that officials do not have the audacity, opportunity, or desire to become corrupt.”

The Report fails to specify the “breeding grounds”, but the present approach of fighting corruption seems to have departed from the harsh and draconian past practices of hanging corrupt officials in their hundreds and appears more realistic. The emphasis now is more on prevention – “steps to ensure that officials do not have the audacity, opportunity, or desire to become corrupt” -- while punishments are not done away with.

One point the Report notes with great satisfaction is that under Xi’s leadership the party “achieved major theoretical innovations, which are encapsulated in the Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” And it is also made clear that this ‘Thought’[3] is, and expected to remain as, the basic guideline for the entire range of the CPC’s (and obviously the government’s) work for the whole of 21st century. So let us try and decode this crucial political formulation, which holds the key to understanding contemporary China.

‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’

To view the whole thing from a proper perspective, we need to begin at the beginning and then move up to the present.

State capitalism

Taking the cue from Engels, Lenin and Mao wrote about state capitalism in their specific contexts (both were capitalistically underdeveloped societies) as a necessary bridge to socialist economy, where land, factories and other means of production belongs no longer to private owners, but to the whole people.

In “Tax in Kind” (1921) Lenin wrote:

“The state capitalism, which is one of the principal aspects of the New Economic Policy, is, under Soviet power, a form of capitalism that is deliberately permitted and restricted by the working class. Our state capitalism differs essentially from the state capitalism in countries that have bourgeois governments in that the state with us is represented not by the bourgeoisie, but by the proletariat, who has succeeded in winning the full confidence of the peasantry.” (Emphases in the original)

In China, development of capitalism was at a much lower stage compared to early Soviet Union. Here Mao called for a broad united front with indigenous capitalists in order to develop state capitalism as ‘the only’ means of transition to socialism in the given concrete conditions. (See Box) This was a somewhat different ball game compared to the Lenin’s NEP, conditioned by the very different class alignment and trajectory of the Chinese revolution. Before 1949 the Chinese national bourgeoisie, in contrast to the comprador bourgeoisie closely allied with imperialist and feudal forces, was an important though vacillating ally of the communist party in the struggle against feudalism and imperialism. After liberation, the CPC carefully nurtured this delicate relationship, as indicated in the document referred below.

In mid-1960s the socialist state in its infancy fell prey to the infantile disorder of left-wing communism in the name of Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. Following the collapse of the former and withdrawal of the latter, particularly after Deng Xiaoping took charge in late 1970’s, the party veered around once again to the framework of state capitalism, i.e., unleashing the productive forces of capitalism, this time by adopting a modified version of the LPG (Liberalization-Privatization-Globalization) paradigm under strict state supervision, so as to help develop the material basis of socialism.

However, Deng went much further than Mao, and his followers perhaps too far, as it would appear in hindsight. As part of the opening up, foreign capital was lured with cheap labour, raw materials and infrastructure to invest massively in China. A growth ‘miracle’ happened at a huge cost of brutal exploitation of workers, rapid rise in wealth and income disparity, unbridled corruption and so on.

Meanwhile, the CPC replaced the candid expression State Capitalism first with “Socialist Market Economy” and after some time, with an even more clouded term: “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”. In practice, both policy formulations meant progressively more freedom to market forces and deeper collaboration with domestic and foreign big capital. Correspondingly, the party stopped using terms like Dictatorship of the Proletariat or People’s Democratic Dictatorship, presumably because these might scare away private investors and Western governments, whose support was vital for success of the new pro-globalisation policy. Instead, it silently put in place an elaborate, high-tech and dreadfully efficient governance system with 360-degree party-state surveillance and control over the entire populace.[4]

This in barest outline has been the process of evolution -- and now constitutes the essence of – what is better called, given the complete and purportedly permanent merger of an omnipotent ruling party and an authoritarian state, Party-State Capitalism.

In October 2020 a concerted campaign to “block the disorderly spread of capital” – as the CPC Politburo put it – was launched. Financial disciplinary measures on an unprecedented scale were taken against some of the most well-connected billionaires like Jack Ma and top corporates. This was followed up with an elaborate mechanism of financial monitoring and control including setting up of party units in industrial and commercial establishments. However, it is recognised by both the government and the business world that the anti-monopoly drive is more in the nature of a belated corrective within the broad framework of party-state capitalism than a real crackdown. There is nothing socialistic about it, but it does demonstrate something. The CPC is careful and determined not to allow the rise of a politically dominant oligarchy as the ruling class, like it happened in Russia. Unlike in India and many other countries, in China the state is not exactly dictated to by well-connected wealthiest corporates. The party-state retains the political command and initiative to decide when and how to promote capital in which sectors and to what extent, sometimes even by allowing them to flout some regulations, and when – with changes in situations and priorities – to pull the strings with full might of the state machine.[5]

The Only Road for The Transformation of Capitalist Industry and Commerce

“… Some capitalists keep themselves at a great distance from the state and have not changed their profits-before-everything mentality. Some workers are advancing too fast and won't allow the capitalists to make any profit at all. We should try to educate these workers and capitalists and help them gradually (but the sooner the better) adapt themselves to our state policy, namely, to make China's private industry and commerce mainly serve the nation's economy and the people's livelihood and partly earn profits for the capitalists and in this way embark on the path of state capitalism. …

“It is necessary to go on educating the capitalists in patriotism, and to this end we should systematically cultivate a number of them who have a broader vision and are ready to lean towards the Communist Party and the People's Government, so that most of the other capitalists may be convinced through them….

“Not only must the implementation of state capitalism be based on what is necessary and feasible … but it must also be voluntary on the part of the capitalists, because it is a co-operative undertaking and co-operation admits of no coercion. This is different from the way we dealt with the landlords.”

Party-state and Civil Society

Regulated Democracy

Genuine democracy is a crucial touchstone to test the authenticity of socialism in any country that calls itself socialist (irrespective of stage). Does China pass this test? Every China-watcher who is not blind knows it does not. But the CPC claims that its “Whole-Process People’s Democracy”[an unwieldly term used in the Work Report] is better than the Western system, in which parties allegedly focus only on promises and winning races instead of governing well. The Chinese system on the other hand claims to focus mainly on good governance, efficient delivery system, and “integration of people’s democracy with the will of the state”. That is to say, the state does not represent the people’s will, it has its own separate (and supposedly superior) “will” and the two need to be combined. This is definitely a far cry from Mao’s celebrated “from the masses, to the masses” legacy -- the party’s basic source of strength in its prime -- where people’s wishes and opinions were regarded as the starting point or primary inputs for policy-making by the party. By contrast, what is envisaged today is a patron-client relationship based on an assumed social contract: the patron (the state) takes care of the material well-being of the clients (the citizenry) in return for absolute obedience.

Semantics apart, the plain truth is that the surveillance party-state denies the people’s fundamental rights to freely air their views or take to peaceful agitations; that the working masses are not regarded as masters of their own destiny and the party behaves like masters/guardians (sometimes benevolent, at other times repressive) of the people. The state in other words remains “a power, arising out of society but placing itself above it, and alienating itself more and more from it”[6], with the party as the arbiter of China’s destiny. Thus “Whole-Process People’s Democracy” militates against and ultimately negates the foundational Marxist concept that under socialism the people take their destiny in their own hands.

Social Fairness without Freedom?

The Report promises “social fairness and justice” but in practice flatly denies them for women who demand freedom and gender justice, religious/ethnic minorities and Queer communities.[7] The same holds true for virtually all kinds of protesters. A recent case in point is that of Jack Yao, a member of the CPC.

Like many others, Yao lost access to his savings in a banking fraud. He took active part in organizing protests online and on streets. The former was promptly taken down from the net and the latter suppressed. The authorities did not deny that the grievances were genuine and the protests were totally peaceful. But they never acknowledged this, although after prolonged protests some redressal measures were initiated. As Yao said, referring to the threatening phone calls he frequently received from the police, “ Their overriding message is – do not make trouble…. When you try to defend your rights, they try to maintain social stability.”

This simple statement of an ordinary party member offers us a glimpse of the bigger picture. Exclusive emphasis on social ‘stability’ to the exclusion of the right to protest and even absolutely peaceful assembly and suppression of all dissent actually demonstrates a deep-seated paranoia of the authoritarian party-state that fears a free people and public dissent. For the powers-that-be, Social Stability-National Security is the overriding concern, the first-named being dubbed “the foundation for a prosperous future”. Attacks on civil liberties and human rights by the “qiangguo” or powerful state is then justified as necessary for the greater cause of national rejuvenation and prosperity.

Nationalism in the international arena

Since a country’s foreign policy is largely an extension of its domestic policy, one cannot but ask, how will this rejuvenated nation conduct itself in the international arena? To this trillion-Yuan question there is no easy answer. What we do know is that nationalism in China today, unlike the people-first patriotism of the first three post-liberation decades, is far removed from revolutionary proletarian internationalism. Essentially it is Han nationalism which, like Great-Russian chauvinism, boasts an imperial past. We also know that Big Capital, the main locomotive of economic progress in this country, has expansionism written into its genetic code and that influential sections of China’s large upwardly mobile middle class are eager to see the nation as a formidable player in both global economy and big power politics. Moreover, such impulses from the past and the present are reinforced by current geopolitical compulsions. In its determined drive to break through the full spectrum, offensive containment policy pursued by the US and its close allies, it may prove difficult for China to never cross the fine line between defence and offence in economic, diplomatic and even military matters. Whether the challenger against American domination remains true to its foundational commitment, “We will never seek hegemony” – first articulated by Mao and Deng[8] and specifically reiterated by Xi twice in last four years[9] – will be keenly observed by friends and foes of China in the years to come.

The Way Ahead

“As a major developing country,” the Work Report declares, “China is still in the primary stage of socialism and is going through an extensive and profound social transformation.” So what are the tasks on the party’s agenda?

“… We will make sure that our implementation of the strategy to expand domestic demand is integrated with our efforts to deepen supply-side structural reform; we will boost the dynamism and reliability of the domestic economy while engaging at a higher level in the global economy; … see that the market plays the decisive role in resource allocation and that the government better plays its role.

“We will deepen reform of state-owned capital and state-owned enterprises (SOEs); accelerate efforts to improve the layout of the state-owned sector and adjust its structure; work to see state-owned capital and enterprises get stronger, do better, and grow bigger; and enhance the core competitiveness of SOEs. [This is a welcome policy orientation, something which India would do well to emulate and adapt, but surely the Company Raj will never allow it to.]

At the same time,

“… We will provide an enabling environment for private enterprises, protect their property rights and the rights and interests of entrepreneurs in accordance with the law, and facilitate the growth of the private sector…

“We will reinforce the systems that safeguard financial stability, place all types of financial activities under regulation according to the law, and ensure no systemic risks arise … [and] increase the proportion of direct financing.[10]

“We will take stronger action against monopolies in pursuing economic growth, we must continue to focus on the real economy. We will … move faster to boost China’s strength in manufacturing, product quality, aerospace, transportation, cyberspace, and digital development … and move the manufacturing sector toward higher-end, smarter, and greener production …”

Notable here are the efficiently planned shifts and readjustments in economic policy. From Deng’s “Let some people get rich first” (so that economic growth is stimulated by increased production and consumption) to restricting monopolies that may have played their role as growth engines in the past, but are now obstructing the development of small entities or start-ups; the shift of focus in manufacturing from quantity to quality; and progress (albeit rather gradual) towards environment-friendly techniques in all productive activities – such are some good examples. The Report further states,

“We will continue to put agricultural and rural development first, pursue integrated development of urban and rural areas, and facilitate the flows of production factors between them. … With these efforts, we will ensure that China’s food supply remains firmly in its own hands.” [A real concern, shared by all poor and developing countries, given the growing control over every aspect of global food production (including seeds, fertilizers, insecticides, water bodies, farmlands, in some cases even farmers themselves) and trade by a handful of MNCs.]

Overarching all these commitments is the assertion that “Achieving common prosperity is a defining feature of socialism”. Over the last few years, the party and the government have been harping on this theme with much fanfare and modest success. Between 2012 and 2020 China’s Gini Coefficient declined slightly from 47.4 to 46.8 (in the US it was higher at 49 in 2020).

However, such policy decisions do not seem to be mere phrase-mongering, sincere efforts are visible. But the story is very different when it comes to issues like human rights, including labour rights, and religious freedom.

The Report advocates “a Chinese path of human rights development”. In plain English, the rights are not fundamental and inalienable, they are allowed strictly within limits set by authorities. And for certain categories like Uyghur Muslims, they are virtually nonexistent. The party advocates a “distinctively Chinese [i.e., majoritarian Han nationalist] approach to handling ethnic affairs” based on “the principle that religions in China must be Chinese in orientation”.

The pitribhumi-punyabhumi discourse in China too! In fact, un-Chinese names (Mohammed, for example) wearables (skull cap) and personal appearances (a certain style of beard) etc. are not tolerated. This trajectory that runs from coercive hegemonisation to ethnic cleansing in the name of nationalism is now so familiar to us in India. The party-state also takes upon itself the responsibility of providing “active guidance to religions”. Clearly, this is a bizarre euphemism for blatant state interference in ‘un-Chinese’ personal faith/religious affairs, as opposed to complete separation of state and religion i.e., genuine secularism (which the report rejects as a western notion) and respect for the individual’s free choice on the question of faith.

With socialism being defined primarily in terms of communist party leadership over the state, which in turn is reduced increasingly to the centrality of the ‘core’ leader, and capitalism predominating over aspects of socialism in the economy, the protracted contention between socialism and capitalism that Mao had predicted over six decades ago seems to be culminating more and more in the rise and consolidation of what we may perhaps call “Capitalism with Chinese Characterics”.

Notes:

1. As we all know, soon after the Congress, wide-spread protests on this issue rocked the country, prompting the government to partially relax the restrictions.

2. The two-term limits for the posts of CPC General Secretary and President of China were removed in the last CPC Congress (2017) and the National People’s Congress (2018) respectively. “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” was already written into the Constitution in the 19th Congress (2017). This time around, an amendment to the Party Constitution calls upon party members to “more conscientiously uphold Comrade Xi Jinping’s core position on the Party Central Committee and the Party as a whole” and makes it “an obligation for all party members” to “follow the leadership core”.

3. Xi Jinping Thought. In typical Chinese symbolism, ‘Thought’ stands taller in hierarchy compared to ‘Theory’, e.g., ‘Deng Xiao Ping Theory’. Xi is the first leader after Mao to be accredited as one who gave China a new ‘Thought’ – a comprehensive political philosophy to guide the party for a whole new era or age, not just a theory on a particular topic suitable for a given period.

4. As in the past, this is supported by a nominally independent but actually party-controlled mechanism of multilayered People’s Congresses. The latter serves to provide a democratic appearance or cover to hide the authoritarian essence of the virtually permanent one-party rule (the bipartisan system in the USA also covers up and shields the dictatorship of the bourgeoise, but far more efficiently) and help manufacture consent in favour of policies and measures decided at the highest echelons of party-state power.

5. For details, see 100 Years of CPC: Great Legacy, Grave Concerns Part III, by Arindam Sen, Liberation, November 2021.

6. Engels in Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

7. For our criticism on this score, see 100 Years of CPC: Great Legacy, Grave Concerns Part III, by Arindam Sen, Liberation, November 2021

8. On April 9, 1974 Deng Xiaoping, then Vice Premier of China, led the first high-level Chinese delegation to the Sixth Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) after the restoration of China’s lawful seat in the United Nations. In his internationally acclaimed speech he said, “China is not a superpower, nor will she ever seek to be one. If one day China should change her colour and turn into a superpower, if she too should play the tyrant in the world, and everywhere subject others to her bullying, aggression and exploitation, the people of the world should identify her as social-imperialism, expose it, oppose it and work together with the Chinese people to overthrow it.” It was a written speech, and these words had been pre-endorsed by Mao.

9. “China’s development does not pose a threat to any country,” Xi said at a conference marking 40 years of market reforms in Beijing on December 18, 2018. At the opening session of the 20th Congress, he repeated the commitment: “No matter what stage of development it reaches, China will never seek hegemony or engage in expansionism”

10. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which is more stable and long-term compared to Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI).