Fascism’s Spatial Geographies

In October 1922, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party staged a march on Rome. Through this march, Mussolini seized power in Italy and inaugurated the first self-proclaimed fascist government in the world. Its consequences were far-reaching. Italian fascism inspired Adolf Hitler and the two fascist leaders went on to wreak havoc in the world, waging war and particularly targeting Jews and Communists.

It has now been precisely one hundred years since that march and unfortunately, we do not find fascism dead and buried. On the contrary, fascistic tendencies dominate authoritarian populisms all over the world, while the latter’s Indian chapter has a distinctly fascist character.[1] Standing at this juncture in Indian history, it is important to remember Italian and German fascism in order to draw historical lessons as well as to trace key genealogies. Indian fascism – represented today by the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliate organizations including the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) – was deeply inspired by the Italian and German models.[2]

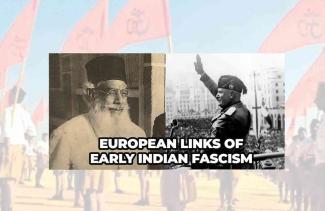

Clear historical connections can be traced between the leaders and organizations espousing Hindu supremacist ideologies during the first half of the twentieth century and their fascist counterparts in Europe. Most significantly, there are records of actual meetings between the Hindu Mahasabha leader Dr. B.S. Moonje and Benito Mussolini in 1931. In this article, we will go over the Moonje-Mussolini connection, and look at what transpired in Indian politics before and after these meetings. This will help us arrive at a clear sense of the European connections of Indian fascism.

In order to develop a thorough historical and theoretical understanding of Hindu supremacism, one needs to grapple with three sets of issues, I suggest. First, one needs to understand the factors that produced the section of Brahmins who pioneered Hindu supremacist politics in colonial India. Who were they, and what made them invest so deeply in developing this political tendency?

Second, one needs to trace the political, intellectual, and cultural currents – both Indian and global – during the late colonial period and situate the growth of fascist ideas within them. In other words, what were the ideas that the early Hindu supremacist leaders thought through in the process of arriving at their formulations? Thirdly, one needs to trace the ideological, strategic, and tactical shifts within Hindu supremacist politics since the 1947 to pin down the factors that eventually allowed the Hindu supremacists to emerged as the dominant force in Indian politics. This article marks an attempt at grappling with the second question.

The Mussolini Connection[3]

Marzia Casolari rightly suggests that the interest of Indian Hindu nationalists in fascism and Mussolini can hardly be considered as dictated by an occasional curiosity, confined to a few individuals, rather, it should be considered as the culminating result of the attention that Hindu nationalists, especially in Maharashtra, focused on Italian dictatorship and its leader. To them, fascism appeared to be an example of conservative revolution. This concept was discussed at length by the Marathi press, right from the early phase of the Italian regime.

From 1924 to 1935 Kesari regularly published editorials and articles about Italy, fascism, and Mussolini. These Indian observers were convinced that fascism had restored order in a country previously upset by political tensions.

In a series of editorials, Kesari described the passage from liberal government to dictatorship as a shift from anarchy to an orderly situation, where social struggles had no more reason to exist. The Marathi newspaper gave considerable space to the political reforms carried out by Mussolini, in particular the substitution of the election of the members of parliament with their nomination in 1928.

Kesari quoted at length from “The Recent Laws for the Defence of the State” which emphasised, on the importance of the National Militia, defined as “the bodyguard of the revolution”. The booklet continued with the description of the restrictive measures adopted by the regime: a ban on the “subversive parties”, limitations to the press, expulsion of “disaffected persons” from public posts, and, finally, the death sentence.

The first Hindu nationalist who came in contact with the fascist regime and its dictator was B S Moonje, a politician strictly related to the RSS. In fact, Moonje had been Hedgewar’s mentor, the two men were related by an intimate friendship. Moonje’s declared intention to strengthen the RSS and to extend it as a nationwide organisation is well known. Between February and March 1931, on his return from the round table conference in England, Moonje made a tour of Europe, which included a long stop-over in Italy.

Moonje in Italy

The Indian leader was in Rome during March 15 to 24, 1931. On March 19, in Rome, he visited, among others, the Military College, the Central Military School of Physical Education, the Fascist Academy of Physical Education, and, most important, the Balilla and Avanguardisti organisations. These two organisations, which he describes in more than two pages of his diary, were the keystone of the fascist system of indoctrination – rather than education – of the youths. Their structure is strikingly similar to that of the RSS. They recruited boys from the age of six, up to 18: the youths had to attend weekly meetings, where they practised physical exercises, received paramilitary training, and performed drills and parades.

The deep impression left on Moonje by the vision of the fascist organisation is confirmed by his diary which recollects a meeting with Mussolini:

I shook hands with him saying that I am Dr Moonje. He knew everything about me and appeared to be closely following the events of the Indian struggle for freedom…. He asked me about Gandhi and his movement and pointedly asked me a question “If the Round Table Conference will bring about peace between India and England”. I said that if the British would honestly desire to give us equal status with other dominions of the Empire, we shall have no objection to remain peacefully and loyally within the Empire; otherwise, the struggle will be renewed and continued…. Signor Mussolini appeared impressed by this remark of mine. Then he asked me if I have visited the University.[4]

Back in India, he started to contact all those who could support his idea of militarising Hindu society. In 1934, Moonje started to work for the foundation of his own institution, the Bhonsla Military School. For this purpose, in the same year he began to work at the foundation of the Central Hindu Military Education Society, whose aim was to bring about military regeneration of the Hindus and to fit Hindu youths for undertaking the entire responsibility for the defence of their motherland, to educate them in the “Sanatan Dharma”, and to train them “in the science and art of personal and national defence”.

Casolari writes that there is an explicit reference to fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in a document that Moonje circulated among those influential personalities who were expected to support the foundation of the school. She also cites evidence of organizational links between such schools in India and Italy.[5] She rightly suggests that these processes initiated by Moonje gradually became key elements of the RSS model.

Who Heiled Hitler?[6]

The sharpest pronouncements in defence of Hitler’s fascism came from VD Savarkar who was active at the same time as Moonje. With Savarkar’s coming on the political scene, from the late 1930s to the Second World War, there was an attempt by the Hindu Mahasabha / RSS to search for newer contacts with the fascist regimes – Germany in particular. Savarkar went public with his admiration for Germany, for example in a speech on ‘India’s foreign policy’ which he gave to about 20,000 people in Pune on August 1, 1938.

In his speech he observed India’s foreign policy must not depend on “isms”. Germany had every right to resort to Nazism and Italy to Fascism and events had justified that those isms and forms of governments were imperative and beneficial to them under the conditions that obtained there. Casolari rightly suggests that Savarkar thought political systems corresponded to the nature of the respective population; a theory that was clearly inspired by a deterministic conception of race, similar to the conception of race then dominant in Europe.

Starting a controversy with Nehru, Savarkar openly defended the authoritarian powers of the day, particularly Italy and, even more so, Germany:

Who are we to dictate to Germany, Japan or Russia or Italy to choose a particular form of policy of government simply because we woo it out of academical attraction? Surely Hitler knows better than Pandit Nehru does what suits Germany different allies among the foreign powers.[7]

Savarkar asserted in a speech in the presence of some 4,000 people at Pune on October 11, 1938, if a plebiscite had taken place in India, Muslims would have chosen to unite with Muslims and Hindus with Hindus. During Savarkar’s presidentship the anti-Muslim rhetoric became more and more radical, and distinctly unpleasant. It was a rhetoric that made continuous reference to the way Germany was managing the Jewish question. Indeed, speech after speech, Savarkar supported Hitler’s anti-Jewish policy, and, on October 14, 1938, he suggested the following solution for the “Muslim problem” in India: A Nation is formed by a majority living therein. What did the Jews do in Germany? They being in minority were driven out from Germany.[8]

Then, towards the end of the year in Thane, in front of RSS militants and local sympathisers, right at the time when the Congress expressed its resolution against Germany, Savarkar stated that in Germany the movement of the Germans is the national movement but that of the Jews is a communal one. And again, the next year, on July 29, in Pune, he said: Nationality did not depend so much on a common geographical area as on unity of thought, religion, language and culture. For this reason, the Germans and the Jews could not be regarded as a nation.

Situating the RSS

The histories of these Indo-European connections and affinities help us situate the RSS within Indian and global politics.

The Hindu supremacists of India drew ideological inspiration from the European fascists. The Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS at the time of Indian freedom struggle espoused an exclusive, xenophobic nationalism, hesitated in their commitment to winning national sovereignty, and upheld Brahminical principles. When India was emerging as a nation through anti-colonial struggle where people from all cultural, religious and linguistic identity united to end the rule of Britishers, the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha were on the other side of the fence, with their idea of a nation based on one religion that would rather be subservient to colonial rulers than unite and fight against oppression. It is this idea of nation based on exclusivity and supremacism of one religious identity over the other (Hindu vs Muslim) that connects the early days of Indian fascism with that of Europe.

Globally, today the RSS and the BJP have pitched themselves as champions of Indian national interests. Their rhetoric has gained legitimacy even in societies which have a rich history of anti-fascist struggle. The Hindu supremacists are gradually showing their true colours on foreign soil too. The recent aggressive march of Hindutva enthusiasts on the streets of Leicester in England is a good example. But we are still quite far from convincing global audiences about the fascist nature of the current regime and from forging powerful anti-fascist alliances that can upstage global Hindutva. Highlighting the lineages of Hindu supremacism even more strongly than before may enable such alliances.

Fascism and Socialism

Last but not the least, revisiting the histories of fascism in Italy and Germany brings to light its direct confrontation with socialism. In a note 'For a Renewal of the Socialist Party' written in 1920, Antonio Gramsci warned about the rise of reactionary forces that emerged as Italian fascism in 1922, in a situation where the Socialist Party fails to lead the proletariat to power. He noted:

The present phase of the class struggle in Italy is the phase that precedes: either the conquest of political power by the revolutionary proletariat, through the transition to new modes of production and distribution that allow a recovery in productivity, or else to a tremendous reaction by the propertied class and the governing caste. All kinds of violence will be used to subject the industrial and agricultural proletariat to servile labor; the attempt will be made to inexorably break the working class’s organizations for political struggle (Socialist Party) and incorporate the organizations of economic resistance (the unions and cooperatives) into the mechanisms of the bourgeois State.

Indeed, the rise of fascism in Europe was a response of national elites to the threat of socialism. So powerful were the socialist currents in inter-war Europe that fascism took on the garb of socialism to appeal to the masses, before brutally crushing workers’ unions, socialists, and communist forces. This confrontation took place in the context of a decadent classical liberal order. Notwithstanding the defeats in Italy and Germany the Left forces emerged as the most powerful opponents of fascism in Europe. No wonder the defeat of European fascism paved the way for a wave of Left victories during the decade following the second world war.

In India, Hindu supremacism emerged in the colonial period – under circumstances in which the Left was yet to emerge as a powerful force in its own right. The former’s rise to prominence in the last few decades has been at the cost of the Indian National Congress more than the Left.

But it is remarkable that despite the Left not being socially and electorally powerful to match the BJP/RSS at this juncture, the latter are ever aware of the Left’s ideological threat. The current regime has been eager to crush Left voices of dissent wherever they exist and made a huge deal of its electoral victory over the Left in Tripura a few years ago. As the Left tries to strengthen a democratic opposition against the current regime, the histories of confrontation between fascism and socialism contain important lessons for us.

1922 Massacre of Workers in Turin, Italy

If in this new phase the Communist Party’s Central Committee proves capable (as it probably will, taking into account the experience of the international communist movement) of developing a tactic adequate to the reality of Italian society and driving open the contradictions created by the Fascist coup d’état, the proletariat will, soon enough, again occupy its historic position, lost after the failure of the factory-occupation campaign in September 1920.

- Antonio Gramsci, Pravda, November 7, 1922

Notes:

1. There is a need to carefully distinguish between the different variants of authoritarian populism we see today. While they share several char- acteristics, and sometimes an emotional affinity, as evident in the Trump-worship of Modi supporters, their genealogies are deeply rooted in na- tional, regional, and local histories which also define the distinctions between them. An understanding of specific characteristics helps us strategize resistance as well as solidarities at local and global levels. Theorizing on this point is however beyond the scope of the current article.

2. Interestingly, the Indian National Congress had identified the fascist tendencies of the RSS quite early on. A confidential report circulated within the Congress, most probably at the time of the first ban of the RSS, after Gandhi’s assassination, noted several similarities between the character of the RSS and that of fascist organisations. National Archives of India (NAI), Sardar Patel Correspondence, microfilm, reel no 3, ‘A Note on the RSS’, undated.

3. This section and the following section draw significantly from the work of Marzia Casolari. Marzia Casolari, “Hindutva’s Foreign Tie-up in the 1930s: Archival Evidence”, Economic and Political Weekly, 22 January 2000, pp. 218-229.

4. Ibid, p.220.

5. Ibid, p.221.

6. Ibid, p.222-225.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.