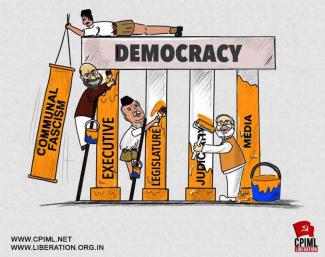

Recent past has witnessed a concerted attack by the Modi government on the Supreme Court. Vice President Jagdeep Dhankar and Union Law Minister Kiren Rijuju have taken turns to publicly berate the collegium system of appointment of judges with the Vice President also castigating the Supreme Court for striking down the National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC) Act in 2015, calling the judgment as being in disregard of the “mandate of the people”. In return the Supreme Court has expressed its displeasure and censured Attorney General R Venkataramani to instruct Union ministers against making such remarks.

The timing of this attack is not difficult to understand. After enjoying a safe run in the Supreme court after capturing power in 2014, the Modi government is conscious of Justice DY Chandrachud becoming the new Chief Justice of India, an office he will occupy for two years during which time at least 19 Judges will be appointed to the Supreme Court. The other reason is made clear in the thinly veiled attack by Rijuju cautioning the Supreme Court not to hear bail pleas or PILs. Incidentally PILs are filed under Article 32 of the Constitution, which Ambedkar declared to be the “very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it”. This comes on the heels of the Supreme Court approving bail to journalists, writers and dissenting citizens like Mohammed Zubair, Siddique Kappan, Varavara Rao and Anand Teltumbde. Incidentally, the tussle between the executive and the judiciary for primacy in appointment of judges is not of recent origin. Post Independence, the executive decided who became judges. After some minor rumblings, the conflict heightened in 1973 when Indira Gandhi, in breach of established convention, appointed the fourth most senior judge as Chief Justice, superseding his three senior colleagues. This was followed by the supersession of Justice HR Khanna clearly as punishment for his dissent in the ADM Jabalpur case. These executive actions established the clear nexus between the appointment of judges and their independence as that of the judiciary. The primacy enjoyed by the executive would last until 1993, when the Supreme Court passed its judgment wresting the power to appoint judges under the collegium system. On coming to power the Modi government attempted to seize this primacy by introducing the NJAC, which came unstuck as the Supreme Court declared it to be unconstitutional. Having enjoyed a pliant judiciary till now, the Modi government has upped the ante against the Supreme Court, most notably by refusing to notify appointments of judges selected by the collegium.

Marx once wrote that “the independent judge belongs neither to me nor to the government”. No doubt there has been hardly any notable change in the class origins of judges, yet interpretations on various rights have undergone distinct changes, sometimes in line with the ruling regime and sometimes against. Even so, there can hardly be a debate against the logic that an independent judiciary can be a thorn in the side for authoritarian regimes. Even during Emergency, when most Supreme Court judges capitulated to the executive, Jst. HR Khanna and several High Court judges ruled in favour of the Constitution.

The current juncture however represents a challenge before the judiciary like never before. Since coming to power in 2014, the Modi government has hardly been asked serious questions by the judiciary despite blatantly encoding Hindutva into the law. Challenges to demonetisation, abrogation of Article 370 and reorganization of the State of J&K, CAA, electoral bonds, among others all remain pending even to this date. Legal scholar Gautam Bhatia argues that this is ‘judicial evasion’ where courts avoid deciding a thorny and time-sensitive question, which effectively is a decision in favour of the government, given that the government benefits from the status quo being maintained. This hits the public perception of an independent judiciary.

Ranjan Gogoi, on demitting the office of Chief Justice, was promptly nominated to the Rajya Sabha by the Modi government which also amended the law to appoint Arun Mishra as the chairperson of NHRC. The Supreme Court also handed down judgments, in crucial matters, that suited the ruling regime’s political project including Babri Masjid, PMLA and more recently EWS. Perhaps this is best exemplified by the Covid cases, where the Supreme Court dismissed PILs seeking relief for migrant workers, by accepting government’s sweeping claims. Retired Supreme Court judge Gopal Gowda declared that “ADM Jabalpur will no longer be remembered as the darkest moment of the Supreme Court. That infamy now belongs to the Court’s response to the preventable migrant crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Even on appointments the Supreme Court capitulated to the executive’s decision not to allow the elevation of Jst. Kureshi to the Supreme Court.

None of this takes away from the justified criticism of the appointment of judges by the collegium particularly nepotism and lack of representation of Dalits, Adivasis, religious minorities, women and other historically oppressed communities. In the face of this assault from the Modi government, the onus is on the Supreme Court to ensure representation and transparency in appointments.

The independence of the judiciary is a basic feature of the Constitution and of paramount importance to a functional democracy. Ambedkar, in the Constituent Assembly, declared that the judiciary has to have that much independence “as is necessary for the purpose of administering justice without fear or favour.” One can only hope that the distinction between the political executive and the sentinel on the qui vive is not eroded to the point of erasure.