Even as nearly one million children of Gaza face a genocidal campaign by Israel driven by relentless bombing and a cruel embargo on essential supplies, the Global Hunger Index 2023 has drawn our attention to the growing pangs of hunger across the world. The GHI 2023 report attributes the alarming global hunger scene to a combination of recent developments like the Covid pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war apart from deeply embedded socio-economic reasons and the rapidly worsening climate crisis. Now Israel’s genocidal siege and invasion of Gaza reminds us how in today’s world hunger can still be inflicted as a form of war. If Israel is not immediately restrained, we will soon witness a veritable famine and thousands of people dying of hunger and thirst in Gaza.

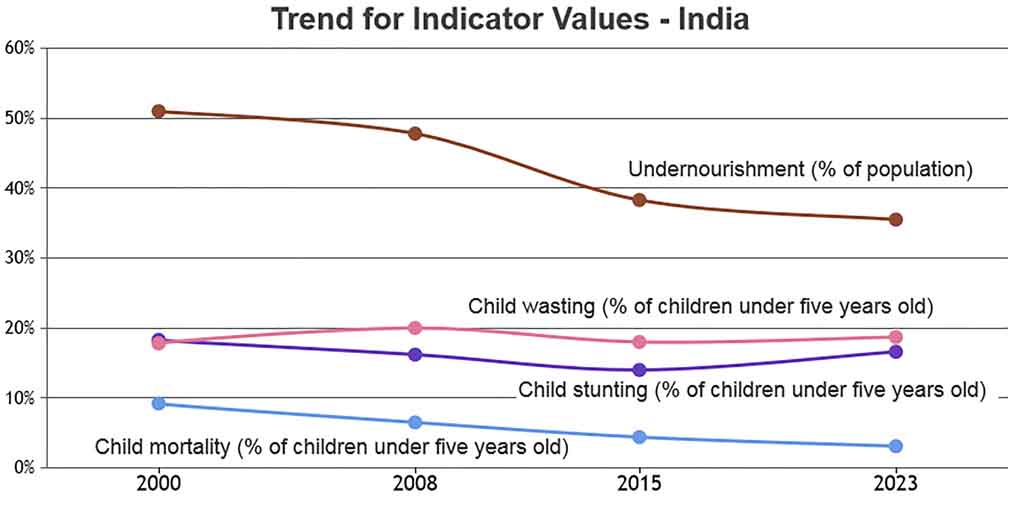

The GHI 2023 report indicates a general stagnation and even reversal on the front of combating hunger. The hunger index is calculated as a combined measure of four factors – undernourishment (among children as well as adults), child stunting (percentage of children below five years of age with low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition), child wasting (percentage of children below five years of age with low weight for their height, indicating acute undernutrition) and child mortality (the mortality rate of children under the age of five). The two most critical regions of the world in terms of the spread and scale of hunger are South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa with a GHI value of 27.0, way above the global average of 18.3.

The biggest contributor to South Asia’s alarming situation is none other than India which has been steadily slipping in GHI rankings over the last one decade. With a GHI score of 28.7, India now stands at 111 out of 125 countries. Each of India’s South Asian neighbours fares significantly better than India – Pakistan ranks 102 with a GHI value of 26.6 while Nepal (GHI 15.0) and Bangladesh (GHI 19.0) have made remarkable progress occupying the 69th and 81st positions, respectively. Sri Lanka, of course, still has the best record in South Asia with a GHI score of 13.3 and the 60th rank. Among the four factors making up the GHI index, India has the most alarming child wasting rate of 18.7% which reflects acute undernutrition. The overall GHI score of 28.7 puts India in the ‘serious’ category of hunger-stricken countries. Undernutrition is not just stunting the growth of millions of India’s children; an alarming 58.1 percent of India’s women suffer from various levels of anaemia.

The response of the Modi government to the GHI 2023 report has been similar to its standard response to all such global reports – be it the Oxfam inequality report or India’s alarming decline in terms of press freedom or various other indices or measures of democracy. The Modi government lives in a perpetual denial mode and even contemptuously rubbishes these reports as foreign or western conspiracies. India has been the only country to find fault with the GHI report, but the authors of the report have convincingly rebutted Modi government’s objections. The data used in the GHI report are collected from verified sources including statistical updates issued periodically by concerned countries and studies by various multilateral agencies. The GHI findings are corroborated by other global studies on hunger and food security. The Global Food Security Index report released annually by the British weekly magazine The Economist placed India at 71st position out of 113 countries in 2021 and at 68th position in 2022. While India with 57.2 points was placed at the same level as Algeria, China stood at 25th position with a score of 74.2.

While the GHI report focuses on undernutrition, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality, the GFSI report is based on measures of food security driven by factors like affordability, availability, quality and safety and natural resources and resilience. The problem in India is now not so much with availability of food where India ranks 42 with a score of 62.3 as with affordability where India finishes 80th with a score of 59.3. The lack of affordability can only be overcome by running a powerful public distribution system, stopping profiteering of food and by improving the purchasing power of the common people. The Modi government's policies are taking the country in the opposite direction. While the regime denies the shocking reports of hunger and lack of food security, in election time it projects the claim of distributing ‘free ration’ to 80 crore people as its biggest achievement. This claim itself is the strongest official testimony to India’s abysmal performance as revealed by the global reports on hunger and food security.

One look at the reports focusing on inequality, hunger and the conditions of India’s workers is enough to deflate the hype manufactured around the G20 summit and the celebration over the tag of the world’s fifth largest economy. The government keeps talking of demographic dividends and empowerment of women. The GHI report throws light on the alarming health conditions of India’s children and young women. Add to this the gloom caused by the trajectory of India's jobless, nay job-loss, economic growth and the precarious conditions of India’s young working and job-seeking population and we know how the Indian people are being systematically impoverished and ruined. The question of the Indian people’s right to food and effective and universal food security cannot be reduced to the Modi government’s cynical vote-seeking in the name of ‘free ration’. The GHI and GFSI reports tell us that continued neglect of the agenda of food security is bound to push India into a bigger disaster.