The Many Uses of the Ancient

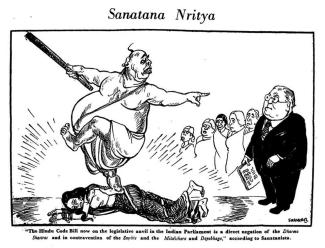

The controversy over Udayanidhi Stalin’s call for the eradication of Sanatana Dharma refuses to die. His comment bewildered a few, shocked many, but satisfied several people as well. He said something that needed to be said. Hindu nationalist politics has repeatedly invoked the Sanatana Dharma – signifying the purported ancientness of Hinduism – to seek legitimacy for its politics and ideology.

Modern Hindu ethnic nationalism has tended to uncritically celebrate ancient Hinduism, thereby giving itself a mythical past, and downplaying the ill-effects of Brahmanical patriarchy which shaped Hinduism’s social, economic and political fabric across centuries. Emphasis on Sanatana Dharma as Indian tradition at its purest and most immutable has also been used to externalize Muslims and Christians, to appropriate Non-Brahmin and Adivasi traditions, and to brand Hindutva’s critics as essentially anti-Hindu or Hindu phobic.

Packaged thus, Sanatana Dharma has been cited as the ultimate justification for a range of conservative policies and court judgments that essentially preserve and strengthen hierarchy, division, and inequality. The Supreme Court judgement on the Ram Janmabhoomi dispute (2019) conveniently declared a merely 150-year-old controversy to have been as old as the ancient religions. The National Education Policy (2020), eager to train children in duties rather than in rights, has expressly earmarked ancient India as a rich source of values and lessons in India’s quest for modern greatness.

Advocate J Sai Deepak’s invocation of Sanatana Dharma in his arguments against the right of women and girls to enter the Sabarimala Temple in their reproductive age is a telling example of the concept’s modern conservative usage. Deepak submitted, during the hearings in 2018, that the deity had rights to practice and preserve its Dharma, including its vow of Naishtika Brahmacharya under Article 25(1) of the Indian constitution and had the right to expect privacy under Article 21. He also submitted that a worshipper could not claim to have a greater right to worship than the rights of the deity whom he or she claimed to worship if he or she had no respect for the traditions embodied by the deity.

The False Promise of Reform

Sanatana Dharma indeed defines the ideological core of Hindu nationalism. And yet, in the wake of Stalin’s remark, Mohan Bhagwat, the chief of the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), who has so far been known for his anti-reservation rhetoric, expressed the need for reservation to undo the injustices meted out to Dalit Bahujan people across centuries! His remark, clearly guided by election-oriented political expediency, drew upon the reformist rhetoric that Hindu nationalists carefully carry in their arsenal.

Indeed, if required, Hindutva enthusiasts can sound as if they wish to rescue ancient Hinduism simply to reform it and bring it up to the needs of modern democratic life. There is nothing more deceptive than the RSS’s promises to reform Hinduism, as evident in its efforts to foreground ‘Muslim exceptionalism’ rather than gender justice (irrespective of religion) as the primary justification for the proposed Uniform Civil Code.

The curious cohabitation of a reformist rhetoric with revivalist overtones has its roots in the nature of India’s modernization. Modernization of religions in the post-Renaissance period often carried a powerful democratic thrust. The remaking of Islam under Mustafa Ataturk in Turkey had a robust reformist bent which impressed many India Muslims of the time including both Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The nineteenth and twentieth century modernization of Hinduism, undertaken under colonial conditions, was however Janus faced.

The reformism of Brahmo Samaj and Prarthana Samaj was counterbalanced by the powerful revivalist thrust of the Arya Samaj and of the Dharma Sabhas which treated reform as a matter of historical contingency rather than of ethical necessity. For the Arya Samaj and later for the Hindu Mahasabha, revivalism became a rallying cry for national freedom. Located in this current, the RSS conveniently took as long as two decades following independence to officially condemn even untouchability. Balasaheb Deoras, under pressure from the emerging wave of Dalit movements, condemned it in his maiden speech as the RSS chief in 1974: “If untouchability is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”

expand

[Brahminism, patriarchy] <Sanatana Dharma> <Hindu Rashtra>

The RSS and the Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have strengthened the stranglehold of caste and gender inequality during its decade in power. While they have claimed to put caste-based politics to an end during the 2014 elections, the BJP in fact did the opposite. Its victory marked a reassertion of upper castes – of Brahmins, Baniyas, Rajputs, Kayasthas – and dominant communities, such as the Jats, in North India.

A post-poll survey of the Centre for Studies in Developing Societies (CSDS) conducted in 2014 indicates that the BJP garnered the support of 82% voters from the Brahmin community, 89% from the Rajput community, 70% from the Vaishya community and 91% from the Jat community in Uttar Pradesh during the election. In Bihar, too, the party employed a tactic similar to their strategy for Uttar Pradesh – pulling non-Yadav Other Backward Castes (OBC) castes towards itself.

Data provided by the National Crime Records Bureau reveals a disturbing increase in atrocities or crimes against Dalits, Adivasis, and women, in recent years. For instance, atrocities or crimes against Dalits had increased by 1.2% in 2021 with Uttar Pradesh reporting the highest number of cases of atrocities against SCs accounting for 25.82% followed by Rajasthan with 14.7% and Madhya Pradesh with 14.1% during 2021. The records also revealed that atrocities against Adivasis had increased by 6.4% in the same year. Crimes against women increased by 83% between 2007 and 2017, and the numbers have not significantly reduced since then.

More than the numbers, it is the sheer impunity of the offenders that strikes you – be it the Hathras atrocity against a Dalit girl (2020), or the incident of urination on an Adivasi man in Madhya Pradesh (2023). Add to that the repression faced by Dalit and Adivasi dissenters in the Bhima Koregaon case since 2018, and more recently in parts of Madhya Pradesh and southern Odisha. And how can we forget the government’s reluctance to conduct the caste census, which is certain to provide a damning indictment of the BJP’s claims of having empowered Dalit Bahujan people?

The Modernity of the Sanatana

Stalin’s remark seems to have hit the nail on the head; that too at a time when democratic forces are striving hard to emphasize the ideological dimension of the 2024 electoral face-off. All good, except that the ongoing debate misses a key point about the modernity of the ancient. Caste and gender discrimination, as we see today, has taken modern forms under capitalism and bourgeoisie democracy, even though they maybe Sanatana in spirit.

India is a country of deep class inequality. According to a report by Oxfam on wealth distribution in India released in the year 2020, the top 10% of Indian population owns 74.3 % of the total wealth, while the middle 40% and the bottom 50% owns 22.9% and mere 2.8% respectively. While we are yet to have a caste census to determine the exact caste composition of these three layers, the naked eye, experiences, and period studies the class divide broadly mirrors the caste and gender hierarchies. The Periodic Labor Force Survey released in 2022 has pointed to an alarming decrease in Women’s labor force participation and engagement in secured jobs between 2005 to 2020.

The emerging stratifications are defined by unequal access to public resources in towns and cities, dispossession from and land and resources, precarious and undignified employment, deep-seated discrimination in institutions, and so on. Certain sections of the Left claim that caste is not a key feature of the emerging divisions: caste has morphed into class. This is far from the truth. On the contrary, the people at the receiving end of the emerging patterns of inequality bear the triple burden of caste, class and gender oppression.

Historically, under circumstances of backward capitalism, caste ties assumed new roles. They became the means for social mobility and securing employment. The literate upper castes could get government jobs through their caste connections. Caste as an institution became crucial even for the development of entrepreneurship. Capitalism, and especially the neo-liberal growth of the last decade has primarily empowered upper castes and men.

The battles against capitalism, democratic deficit and climate change are also battles against Brahminism and patriarchy. These need to be fought highlighting caste-class-gender intersections. Pushing back the resurgent thrust of the Sanatana Dharma is one side of the coin, fighting the modernized forms of the same is another. Unless we recognize the necessity and the urgency of these twin battles in our quest for equality and justice, we run the risk of descending into sophistry and empty rhetoric; all in the name of ideologically challenging the RSS/BJP.