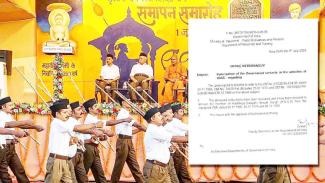

Following a recent directive from the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), issued on 9 July 2024, government employees are now permitted to participate in Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) activities without attracting disciplinary action under the rules of conduct applicable to them.

The ban on government employees participating in RSS activities was imposed in 1966, following a massive anti-cow-slaughter protest at the Parliament, which was supported by the RSS and its political front – the Bhartiya Jana Sangh (BJS). This led to the dismissal of several government employees who were found to be involved with the RSS.

The removal of these restrictions from central government employees by the Union government follows similar moves by the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) led state governments in Madhya Pradesh (2006), Uttarakhand (2008), Chhattisgarh (2015), Haryana (2021) with regard to their respective employees.

The Logic Behind the Ban

On November 30, 1966, the Ministry of Home Affairs (of which DoPT was part until 1998) issued a circular: “Certain doubts have been raised about Government’s policy with respect to the membership or any participation in the activities of the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Jamaat-e-Islami by Government servants… Government have always held the activities of these two organizations to be of such nature that participation in them by Government servants would attract the provisions of sub-rule (1) of Rule 5” of the Central Civil Services (Conduct) Rules, 1964.

“Any government servant, who is a member of or otherwise associated with the aforesaid organizations or with their activities, is liable to disciplinary action,” the circular said.

In order to prevent any dithering and manipulation, the 1966 order was subsequently reiterated through government orders and circulars. On July 25, 1970, the Ministry of Home Affairs again said, “Action should invariably be initiated against any Government servant who comes to notice for violation of the instructions [of November 30, 1966].”

On October 28, 1980, the government of Indira Gandhi issued a circular underlining “the need to ensure a secular outlook on the part of Government servants”, and stressed that “the need to eradicate communal feelings and communal bias cannot be over-emphasized”.

Can Public Servants Participate in Politics?

The 1966 ban came at a time when the relation between government servants and political parties was being clarified by the post-colonial government. The Central Civil Services (Conduct) Rules, 1964, and the All-India Services (Conduct) Rules, 1968, imposed restrictions on involvement of government servants in politics.

Rule 5 of the 1964 Rules is about “Taking part in politics and elections”. Rule 5(1) says: “No Government servant shall be a member of, or be otherwise associated with, any political party or any organization which takes part in politics nor shall he take part in, subscribe in aid of, or assist in any other manner, any political movement or activity.”

The All-India Services (Conduct) Rules, 1968, which apply to officers of the IAS, IPS, and Indian Forest Service, has a similar Rule 5(1).

Prior to these, there was the Government Servants’ Conduct Rules, which were framed in 1949, when Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was home minister. Rule 23 of 1949 was the same as Rule 5 of 1964 and 1968.

Thus, participating in political activities was always prohibited for government employees. The nature of the organizations in question was clarified from time to time as per requests and representations.

Is the RSS a Political Organization?

The RSS is an organization of a peculiar nature. Its structure is murky and deliberately so. It has always claimed to be a cultural organization whereas it has proactively participated in politics through its various frontal organizations – the BJS, the BJP, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bhartiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) and so on.

While the RSS claims to merely be an ideological influence on these, in reality it is much more than that. RSS leaders have nurtured and shaped these organizations at an ideological and organizational level.

The murky nature of the RSS has been used cleverly by the organization to push its agenda forward, including the flouting of the 1966 ban from time to time. The judiciary initially succumbed to its machinations.

The Punjab and Haryana High Court in Chandigarh set aside the dismissal of a government employee who was removed from service in 1965 for his participation in RSS activities, citing lack of material to prove that the RSS was a political party. That’s why the government felt it necessary to reiterate the ban in 1970 and 1980.

Is Ban the Solution?

Notwithstanding whatever we have said above, it is worth asking if banning is a solution, given the widespread influence that the RSS now holds over Indian society.

Here it needs to be clarified that the entire question hinges on the nature of the RSS. If public servants are banned from participating in political activities, then they should certainly be banned from participating in the RSS because of the outright (though denied) political nature of its work and objectives.

Crucially, while the 1966, 1970, and 1980 circulars also mentioned the Jamaat-e-Islami as an organization of a “political” nature, the July 9 circular removes that tag from only the RSS. This means that the Jamaat-e-Islami still remains an organization whose activities are categorized as “political”, and government officials cannot take part in them.

Thus, the government’s move is nothing but a way of normalizing the RSS.

The RSS has historically been opposed to the constitutional democratic framework of Indian state and society, not even accepting the Indian flag. Institutional capture and corporate support are two key ways in which the RSS has legitimized itself. The 9 July circular marks another step towards institutional capture by the RSS and must be opposed by all democratic forces.